You describe your pieces as both pictorial and performative. How do these two dimensions interact in your creative process?

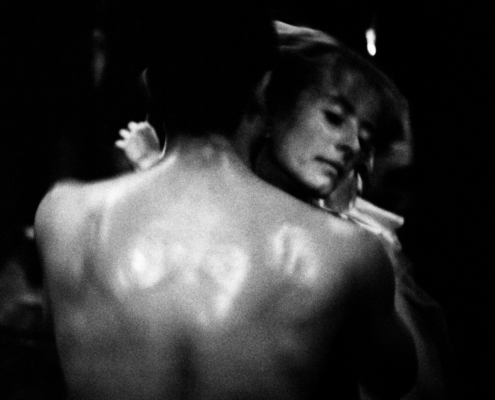

In the case of painting, it functions almost as a literal representation of theory; it’s like writing, narrating my own research through images. But performance, unlike painting, is carried out in reality, and that’s what drew me to it. Painting, in the end, is an image, a representation of something. And I believe that in that process, many symbols and meanings are lost. For me, it was important that it wasn’t just about representing an image, but that in some way, the representation could have a direct impact on reality. In the place where I grew up, there were no art spaces like cultural centers or contemporary art museums, there were no contemporary art exhibitions. I encountered that world much later, and I became interested in bringing all the knowledge I had gained through painting into a more direct space of dialogue: performance. Performance is the act of working with your body, that is the raw material. It’s a form of immediate conversation. We all have a body, whereas painting, I feel, is surrounded by different meanings, more tied to the long history of art, and on the other hand, to spaces where works hold economic value, like the market, museums, or galleries. For me, the theory that can be contained in a painting is activated through performance in the body. It’s like bringing theory into practice.

An essential part of your work seeks to break away from the normative truths of sex and gender. How do you experience that subversive gesture within an art system that often still operates under binary and conservative structures?

I believe we are always exposed to criticism, often even mocking criticism. When we lack the tools to understand certain positions or ideas, we tend to attack them, and that’s why I feel I’ve always been exposed to those kinds of comments and reactions. Any kind of change, whether small or large, generates discomfort. People are usually very comfortable where they are, so any comment or action that pulls them out of that space creates a kind of emotional “earthquake.” In the end, you’re interacting with people, and each person has their own emotions, story, or perspective. I remember, for example, that in one of my first exhibitions (*The Other Sex*, 2018), I presented molds of sexual organs. That cultural space also offered workshops for children, and some parents wanted to break the molds and remove them from the exhibition because they were worried their kids would see them. So, I think you have to let things happen. In that case, let the parents react as they need to. We’re constantly interacting with multiple sensitivities, and for me, it’s a matter of “letting go and receiving.” You can’t control what’s going to happen, you can only be consistent in your own practice. We can’t predict how the audience will respond.

In your artistic practice, your physical body has become raw material and a conceptual tool. At what point did you decide to use it directly as a medium of creation? For example, in the surgical intervention where you removed your “Adam’s rib,” what led you to make that decision? What meanings or inspirations motivated such a radical and symbolic gesture?

In general, all my work is born from a need to find my own freedom. This search is directly linked to the experiences of fear and anxiety I lived through in my childhood, when I began to understand how society functions, how we are kept trapped through fear. That’s why my work seeks to capture small fragments of freedom, especially when I’m able to modify my body and that small chimera becomes reality. Modifying my body goes beyond the symbolic; it transforms deep aspects of my life on a mental and physical level. There’s one particular story that gave birth to this project: One time, while reading tarot with a friend, the Lilith card appeared. She told me, “You really resemble Lilith.” Lilith was the first woman, before Eve, and according to the myth, she was condemned to have a burning vagina and to be unable to bear children. That image sparked great curiosity in me, who could have imagined something like that? I began researching the historical meaning of her figure and found an archetype of a woman punished for her rebellion and desire for freedom. In Latin America, the symbolic weight of religion still operates as a dominant cultural accessory. The figures of Adam and Eve are almost presented as the founding “superheroes” of our story. Even though I don’t believe in God, I recognize how present those images still are. I mention this because, for example, in Peru, when referring to a man’s partner, people often say “his rib”, slang that directly references the biblical myth of Eve being created from Adam. That’s where the idea was born: if Lilith was condemned for rebelling against God and seeking her freedom, how can I narrate another genesis? One where the first two women in history, Lilith and Eve, meet, form an alliance, and free themselves together from Adam. That’s how I created a large-format painting where the two meet, and through their encounter, a new creation is born. As a symbol of this alliance, I imagined a scene where Lilith removes one of her ribs and offers it to Eve, reversing the biblical narrative. And then I decided to take that narrative into the physical realm, to obtain a real rib as archaeological evidence of this new story. That’s why I chose to undergo surgery to have one of my ribs removed. Although this procedure is often done for aesthetic purposes, to reduce the waist, in my case, it was a political act: transforming a medical procedure into a performative action against religious dogma. Removing that “imposed faith” from the body, but also reclaiming my autonomy as a woman.