How do you balance all of your creative activities, as curator, artist and musician?

Ever since I started out in this life, I’ve used a methodology of multiple streams of activity as a means of survival. When I was still in high school, I started a fanzine and then a cassette label and then the first year out of school I started my first proper label, started organising shows and kept on writing, both as the editor of my zine, but also for various music, art and culture papers in Australia. At that time I was also performing in a couple of second wave industrial bands and around 1995 I started to create my first solo music, which was mostly collage oriented and not particularly interesting beyond the interrogation of how juxtaposing ideas can create unexpected relations. So, from the onset I have always worked on many things in the same breath.

In terms of this idea of balance, I’m not sure this is something that I’ve ever really subscribed to. For many years, my life curating and organising far outweighed my time spent making work for myself. I am in no way upset about this, as frankly I draw a great deal of satisfaction from curation and especially from making opportunities for others to share the work that I find inspirational and more over critical to a broader reading of cultures, be they sonic or otherwise.

Can you tell us a bit more about your experience in sound curating?

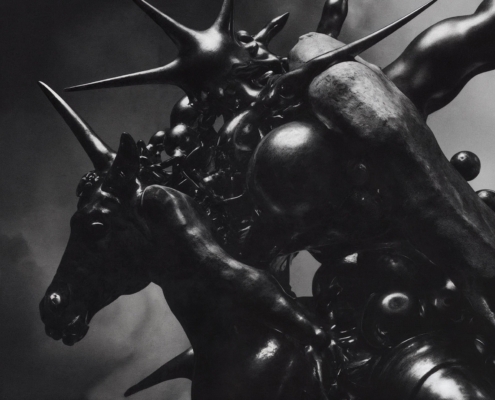

Curation and specifically sound curation is a practice I have explored at various times over the past couple of decades. I’d say the last three years have been the most satisfying in terms of the projects I have untaken. In January 2018 I had the opportunity to present Genesis P-Orridge’s survey exhibition “Loyalty Does Not End With Death”. Working on that show with Genesis was a pleasure and the scope of the exhibition moved far outside of their work in sound and focused more on their radical work around thee Pandrogyne. The past 18 months I spent researching for two exhibitions that were opened early this year at The Substation in Melbourne, Australia. The first was a career long retrospective of the Japanese sound artist Akio Suzuki called “Sense Of Ēko” and the second exhibition was “Reframed Positions”, a major survey of the work of American artist Terre Thaemlitz. Both of these exhibitions took some time to distillate. The nature of the artist’s work is always littered with complexity and in both these cases was deeply conceptual. In terms of the actual works from Suzuki and Thaemlitz, they couldn’t be more in opposition, and I say this as a positive. Each exhibition required some markedly different approaches to unpack the works; some more text based and the other more performative. I think curation is a perverse practice ultimately, its boundaries are amorphous and it’s this quality I find most appealing about it.

Is there a difference between music and sound art in your opinion and if so how would you describe it?

If sound is language, then music is a dialect of sound.

Can you tell us more about your “Room 40” project.

“Room40” is 20 this year. It started out in a time when Australia was still very much removed from the rest of the world, and especially Brisbane where I was living. Initially it was started with three main focuses, to publish works, to present performance programs (and by default to make connections between artists and communities through these events) and to advocate for sound art.