With your profound commitment to craft and materiality, how do you foresee emerging technologies, especially AI, challenging traditional ideas of artistic autho rship and reshaping the very essence of creativity in design?

Michèle: It’s a fascinating time because we’re living in the age of AI. Just yesterday, while we were looking at Tracey Emin’s sculptures and films at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, something struck me. She was encouraging people to forget about AI, to stop focusing so much on it, because in the end, ideas and creativity still have to come from us. But at the same time, there’s no denying something fundamental has shifted in our culture. We don’t fully understand it yet, but it’s happening. Even if AI can generate images or replicate tasks, what really matters is materiality—ideas taking physical form. It’s about expressing what we believe, making choices, and creating something tangible. That’s where design, fashion, and craft come together for me. We can’t pretend AI isn’t part of this moment. People say robots will replace us one day, but that’s not happening yet. Teaching a robot to cut fabric doesn’t change the essence of craftsmanship. It will be a long time before a robot truly understands that.

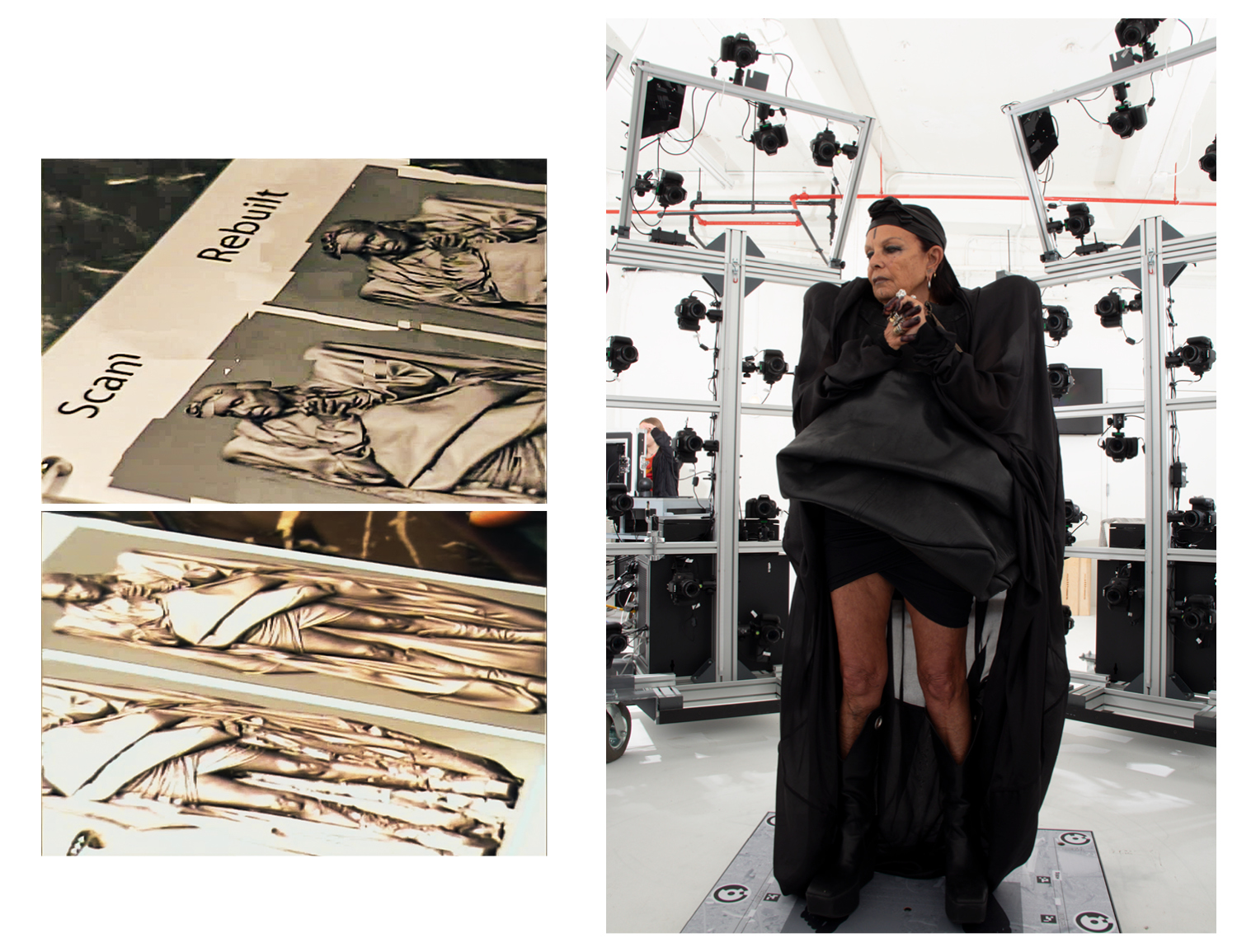

Barry: My robot actually creates jobs for six people, so it’s not replacing humans. Michèle is now overseeing all the Rick Owens production, which has grown from a small operation into something much bigger. I’m not sure I’m trying to make art AI can’t copy, but in the stone sculpture world, it’s a hot topic. I was in Carrara recently and 60 Minutes came to film a segment about stone-carving robots. What I didn’t expect was the ambush—their first question was: “Some say you’re the death of art.” They’d interviewed traditional sculptors in Florence who said Michelangelo would be turning in his grave because of robots. Come on. Those guys have been doing the same thing for fifty years. Every contemporary artist I know embraces technology. Look at Pierre Huyghe—he’s not running from AI. Artists have always used the tools of their time. Even the Egyptians had advanced measuring systems. That myth of Michelangelo freeing figures from marble? Just that—a myth. He used sophisticated tools and scaling techniques. A genius, yes, but he relied on the best technology available. If he were alive now, he’d have twenty robots in his studio. His grand project—the tomb for Pope Julius II—was meant to have 120 sculptures. He finished only 17. He simply ran out of time. Back then artists didn’t have robots but they had bottegas. So that’s basically the same. It has always been about commissioning the work to someone else. Bellini had about 70 assistants supporting him. So, you know, it’s a pretty silly argument.

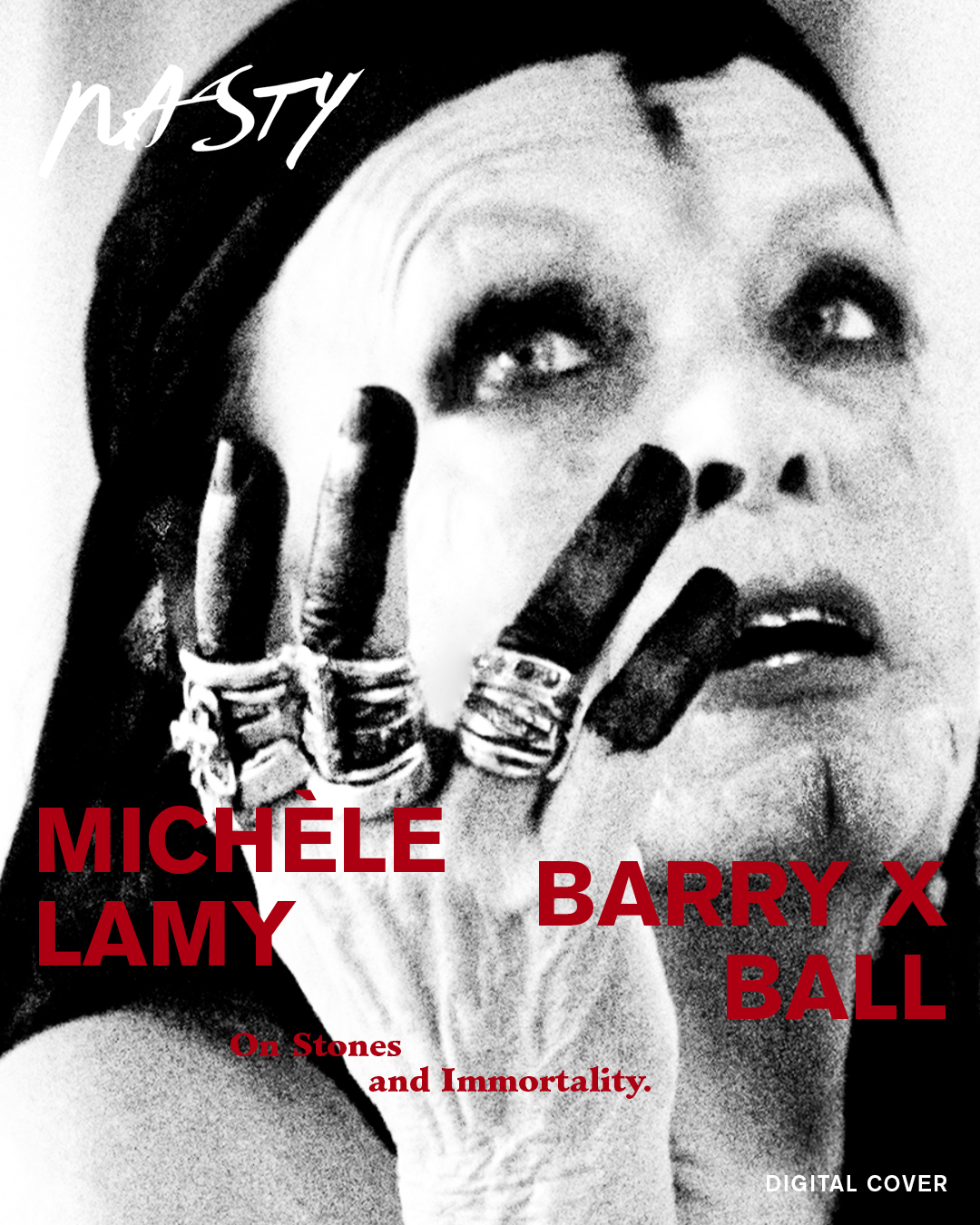

We could say that the black Belgian marble used for Michèle’s bust is just one of many materials you both explore. Speaking of bust portraiture, it remains one of the most enduring forms in art history. What relevance does it hold in today’s contemporary art scene?

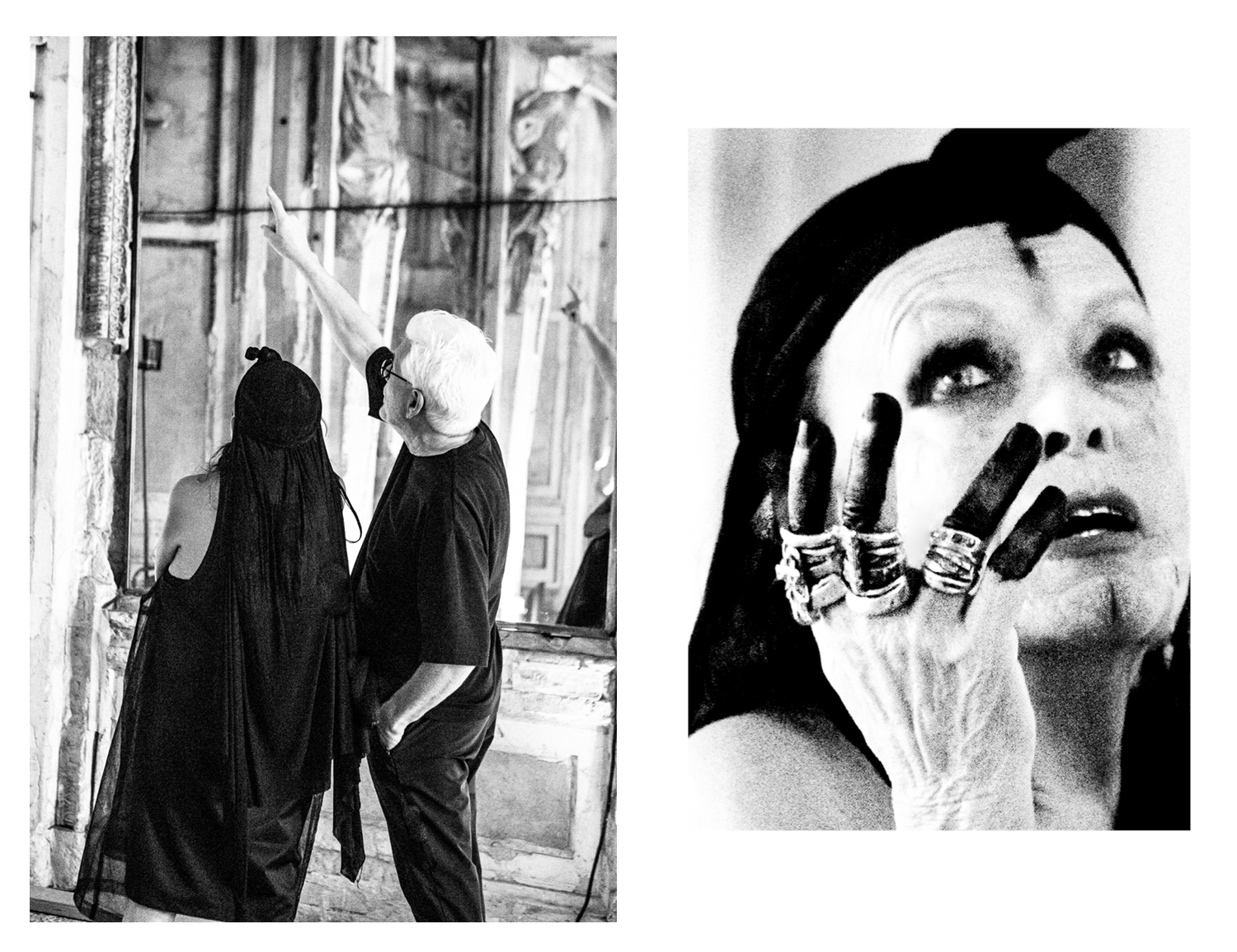

Barry: In the world of contemporary art, there are still a few portrait painters trying to do serious work. But generally, even when figures are involved, it’s not really about celebrating a specific individual. Even in sculpture, portraiture as a way to commemorate someone has almost disappeared. I like the challenge of bringing it back. Of course, it serves a very different purpose now than it did for someone like Marcus Aurelius. I was once in the basement of the Louvre working on a project, and there were about a dozen versions of Marcus Aurelius down there. Back then, his image was spread across the Roman Empire, just like coins. It had a different role in those days. Now we have television, phones, all of that. But I like the idea of revisiting this format and doing something new with it.

Michèle: Comme Calum a dit, je sais que: you are bending time and perception through craft and technology.

So, is that how you achieve immortality? Or is that even the point?

Barry: This is definitely a portrait of our time. She’ll be with us for another 25 or 30 years, but the goal is to capture this extraordinary person right now. Trying to do that in stone—it’s almost a ridiculous undertaking, but that’s what makes it worth doing.

Michèle, what do you see when you look into the eyes of your own double? Did it shift your sense of self in any way or did it confirm something only others could see?

Michèle: I think the scan gave me too many wrinkles (laughing). Right now, we’re all so obsessed with surface and flawlessness. The only experiment that really stuck with me was the one in Mexican onyx, that stone full of holes. I think it’s genius, especially now, when everyone’s trying to smooth everything out and AI is taking over. Choosing a natural material with so much personality already, that’s powerful.

Michèle, you described your process as “ritualistic” — a kind of everyday obsession that builds into magic. Barry, your sculpture process is meticulous, sacred, and slow — almost alchemical. Where does obsession end and devotion begin in your work?

Michèle: Honestly, I don’t really know where to draw the line. What looks like obsession is really just pushing yourself so hard that you might break. But deep down, it’s devotion—it’s connected to pleasure.

Barry: That’s a perfect way to put it. Obsession sounds like something you can’t control. Devotion feels more like a ritual, something you believe in. You set it up to bring pleasure, even if it’s stressful. We’re all trying to do something extraordinary here. No one’s playing games. Look at the fast life she leads, not chasing fame, but chasing something real.

Michèle: I guess I was just born this way. I’m just bread and butter.

What has kept your fire burning after all these years? What’s the drive that still keeps you going?

Michèle: We’re all fighting the fear of death. Even if we don’t say it out loud, that’s what pushes you forward.

Barry: Yeah, we’ve both hit big milestones recently, seventy and eighty. But we’re not slowing down. That said, I find myself admiring less and less of what passes for art these days. The revolutionary spirit is gone. That edge has disappeared. Art feels decorative now, not daring or cutting-edge. But then I look at Rick Owens’ work, he’s always pushing boundaries, inventing new silhouettes and ways of being. That’s what I’m aiming for with my work: creating objects you’ve never seen before. I grew up in 1960s Los Angeles, the edge of the continent and the heart of aerospace. Everyone around me was building something new (jet engines, racing boats, motorcycles) in their garages. The future felt like something we could build. That spirit stuck with me, even after I left my roots. I still believe we can create a beautiful new world.

Michèle: (Pauses, looking at Barry with her silver eyes and a smile)

Barry: I like watching you think for a good fifteen seconds. It’s a lesson for all of us, sometimes, just shut up and think.

Michèle: (Slowly finding her words after laughing) We’ll probably die trying, you know, me and you. But not anytime soon.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Salo-8-by-Alma-Libera.jpg

1071

1600

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2023-11-13 18:40:172024-10-10 16:11:31Saló / Art, ecstasy & extravagance

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Salo-8-by-Alma-Libera.jpg

1071

1600

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2023-11-13 18:40:172024-10-10 16:11:31Saló / Art, ecstasy & extravagance