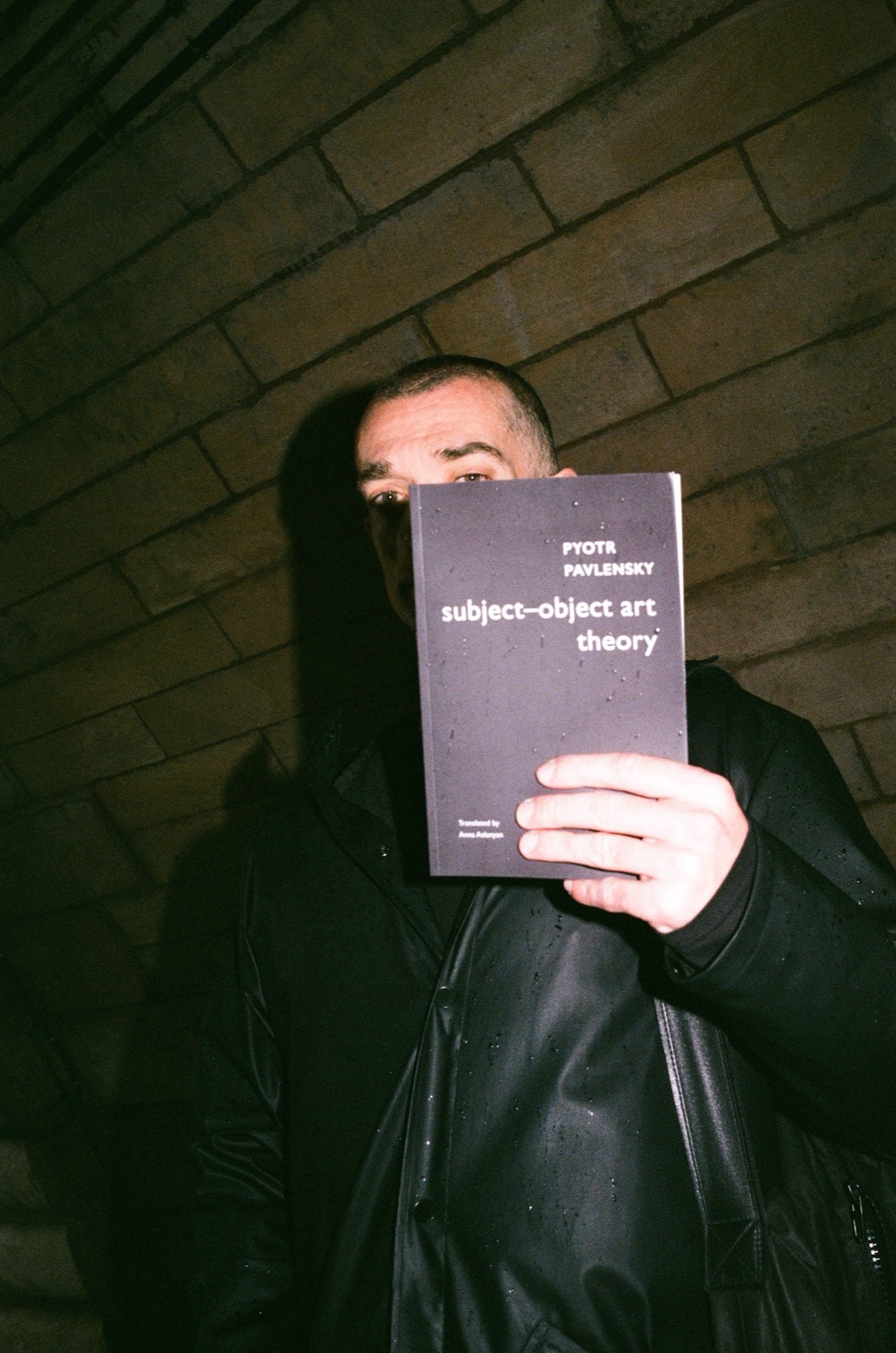

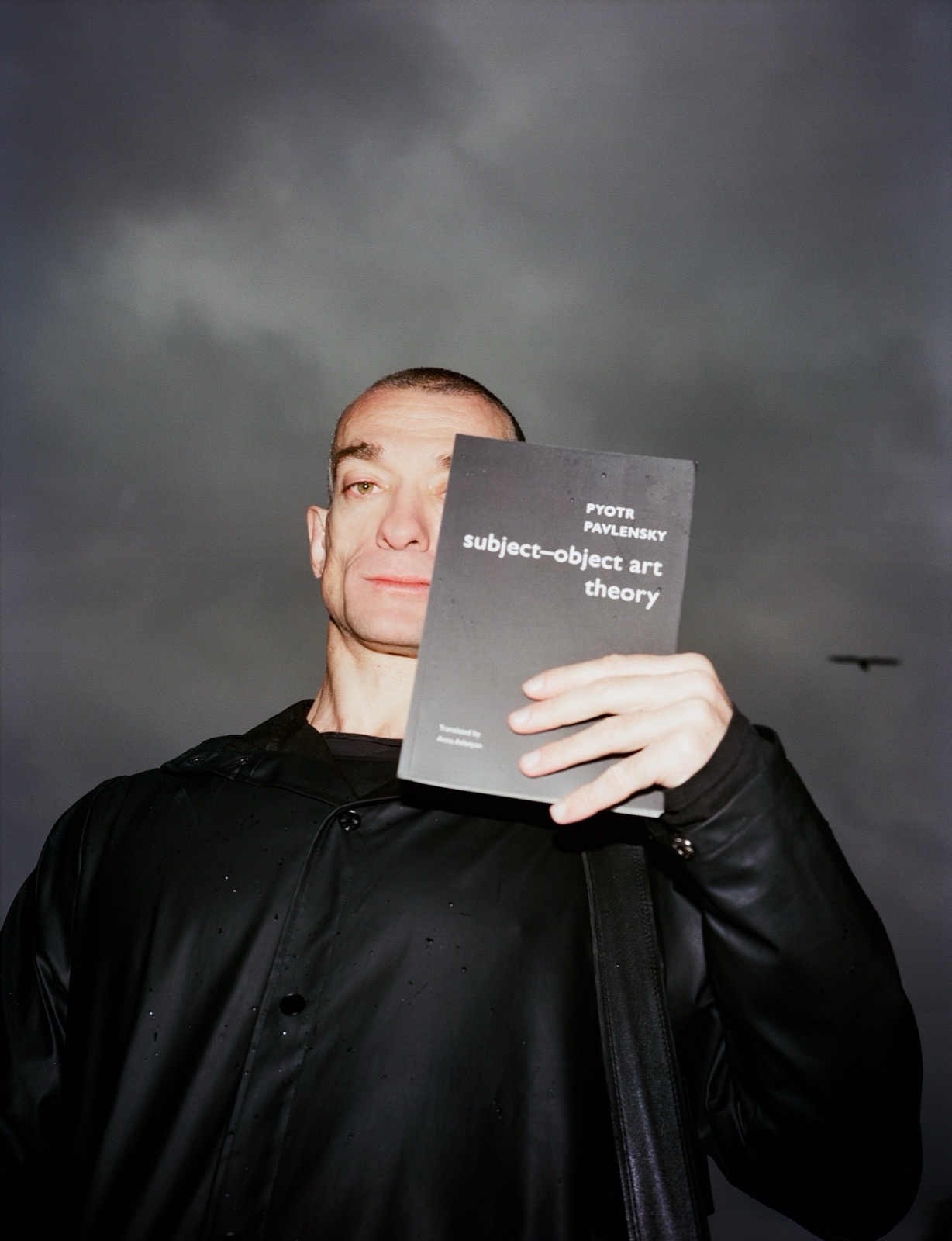

I first encountered Pyotr Pavlensky through a pixelated university Wi-Fi connection, watching him speak in a low, rapid Russian that I could not fully grasp. What reached me instead were his eyes, alert and eroded, sharpened by exile in Paris. I thought I already understood the contours of his practice, the images that had circulated endlessly online, the body as a site of political friction. But the conversation shifted the moment he revealed that his primary artistic reference has always been Caravaggio. The connection felt improbable, almost provocative, until I opened Subject-Object Art Theory, his new book published by Seagulls Books. Only then did the pairing acquire clarity.

The book is neither memoir nor manifesto but a theoretical treatise. It attempts to give a name and a structure to a practice repeatedly misread as performance. Pavlensky starts by dismantling the assumption that “everything is performance”, a claim that, in his view, neutralises artistic differences and collapses practices into a single vague category. To counter this, he proposes the term that anchors the entire essay: subject–object art. The book is arranged around pairings of historical figures, a structure that mirrors Pavlensky’s aim of breaking down binary thinking. These couples of names are not meant to illustrate fixed categories but to expose the fragility of the categories themselves.

Before defining this new artistic framework, Pavlensky returns to a question that has haunted his decade of practice. Is political art produced through political means, or is politics produced through artistic means? This distinction matters because, for him, meaning never exists in the abstract. It always serves something, whether we acknowledge it or not. Art has always been enrolled in the service of power, whether through the monumental propaganda of Napoleon or the ideological engines of Socialist Realism with Lunacharsky, Gronsky and Gorky. In all these cases, art becomes decorative, a visual arm of ideology. What matters is not the style, the quality or the content, but the fact that the artwork performs the function assigned to it by a governing system.

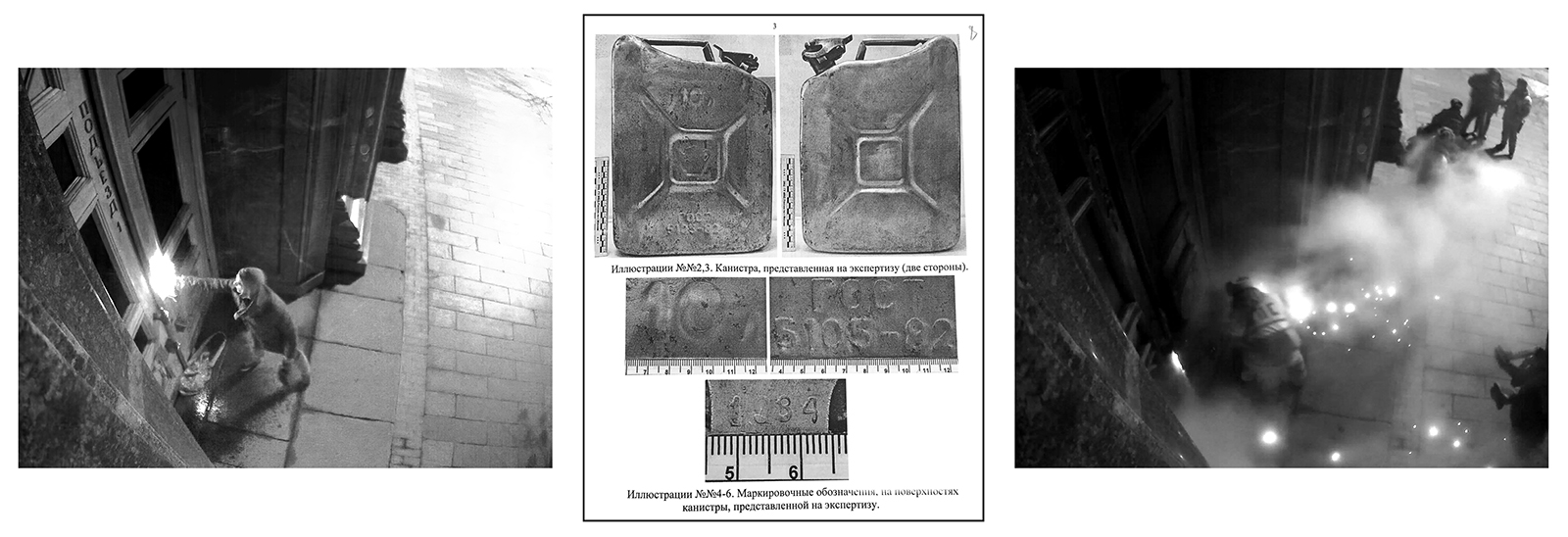

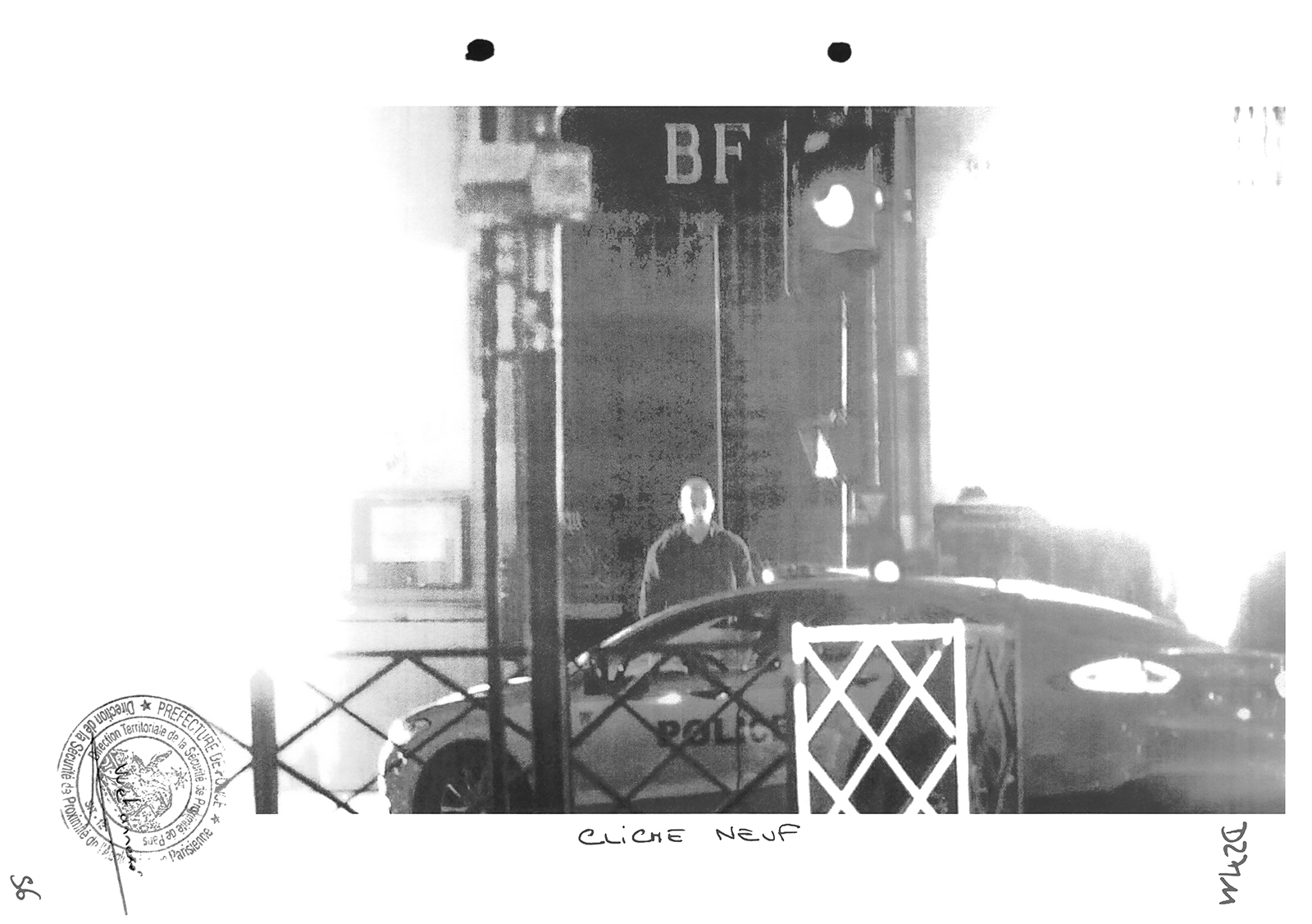

Pavlensky’s intervention lies in proposing a way out of this dynamic. Political art, in his definition, is not art about politics but art that forces the mechanisms of power to become unwitting collaborators. It is an art that operates inside the machinery of control, using its instruments as raw material. Decorative art serves power. Political art compels power to serve art. This reversal is what he calls a turnaround. To illustrate it, he returns to one of his most widely circulated events, Fixation, staged in 2013 in Red Square. A naked Pavlensky sits on the cold cobblestones, his scrotum nailed to the ground with a twenty-centimetre metal spike. The shock of the gesture soon gives way to a stranger image. Motionless and silent, he ceases to resemble a person and becomes almost a sculpture with human skin, an object rather than a subject. The police arrive. They shout orders, but objects do not respond. They call superiors. They wait for instructions. Their authority cannot function in the usual way. They must improvise, negotiate, escalate. In that moment, power begins to generate material for the artwork. Pavlensky insists that this is not metaphorical or symbolic. The reports filed by police officers, the paperwork produced by investigators, the legal proceedings that follow, all become the substance of the work. The institution believes it is suppressing an act. In reality, it is producing it. The focus of the investigation is no longer the artist’s guilt but the creation of new materials that the artist later selects, archives or recontextualises. Power enriches art by fulfilling its own protocols.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/nasty.jpg

919

1500

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2020-07-02 17:32:342020-07-02 17:53:39Mikael Christian Strøbek / The way to a sustainable tomorrow

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/nasty.jpg

919

1500

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2020-07-02 17:32:342020-07-02 17:53:39Mikael Christian Strøbek / The way to a sustainable tomorrow