Your work often engages with lists, numerical sequences, simulations, words, calendars, books, images, and websites, turning them into artistic material. When and how did you begin to consider these as actual materials to work with? Do you perceive a sense of materiality in them?

Materiality is less a property than a conviction. A material is a claim; a wager that something can be made to carry form. It’s easier to see this when you pool it or aggregate it, so often a lot of my work begins with amassing an archive of a particular thing. Everything has a handle if you can find it. With these types of materials, the process is more about articulation than fabrication. You’re just trying to get leverage over some quantity, and if you can do that, anything can be a material. This approach seems obvious to me now, but I only realized it when I built a content management system for archiving my work. The act of deciding what to write in the ‘material’ input field completely reframed the problem for me; as if it somehow gave me permission.

As digital as your work may be, you use both the real world and the digital realm as exhibition spaces. What are the main differences between experiencing your work on a personal laptop screen and seeing it on a screen inside a gallery? As an artist, do you take this duality into account while creating? Conversely, what kind of challenges do you think your practice poses for curators?

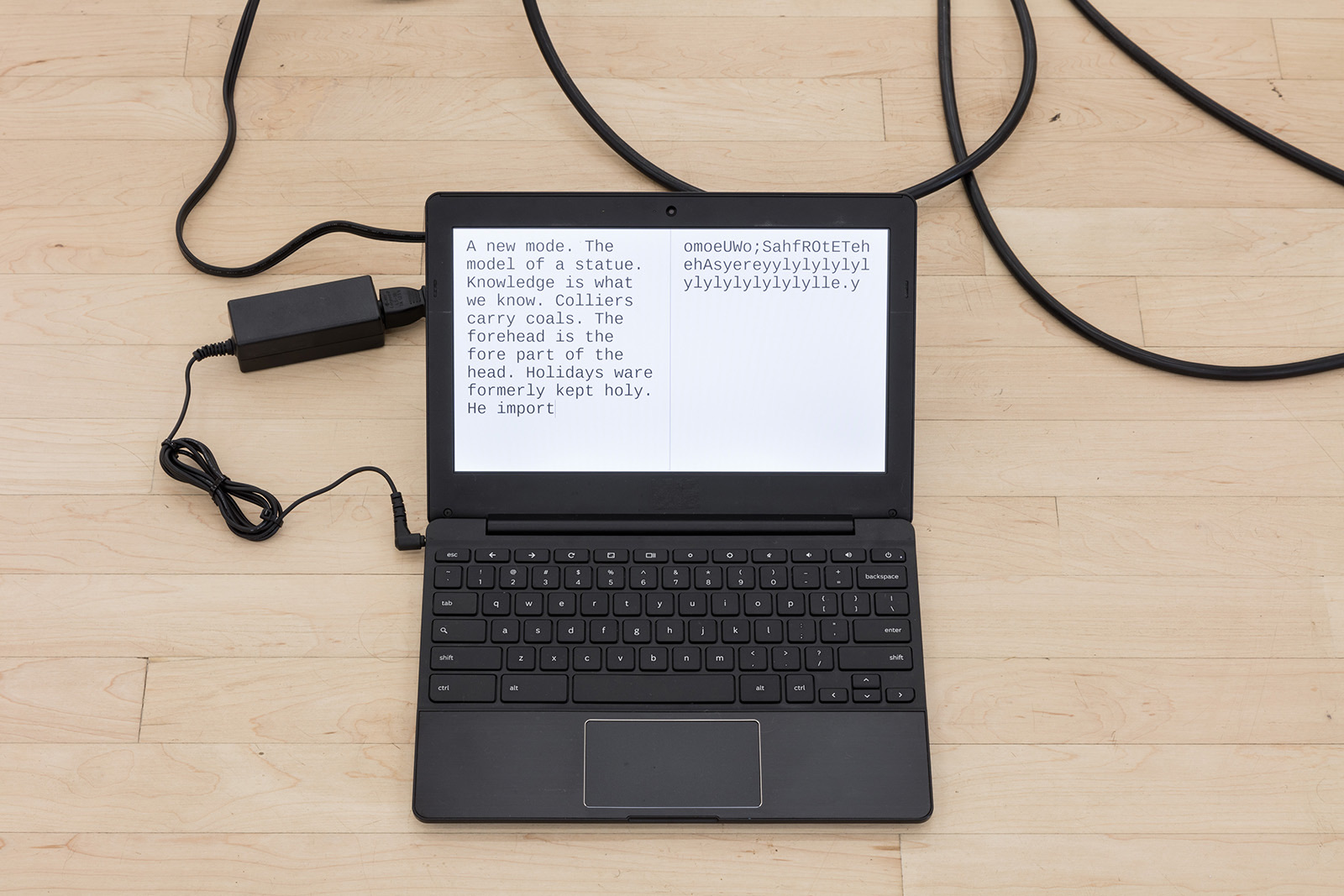

Attention is distributed differently across the contexts. On a laptop, it’s a function of a windowed environment: fragmented and recursive. Maybe you bookmark something for a later that never arrives. Or it comes back to you in the form of a retargeted, recurring ad. You drill down into a topic only to lose it behind a hundred tabs. On your phone, the experience is more modal… content appearing for a moment before you just scroll past or close the app. In the gallery, work can more readily live in the periphery; there’s cross-talk between different pieces. You can modulate things like distance and volume; everything is inherently sculptural. Online, I want the work to live forever, but a gallery show is fleeting: up for a month, then gone, reduced to documentation thereafter. Yet you still have this responsibility to consider how it might age. A collector takes it home to live with it, and it starts to acquire a whole new set of meanings. A book I make may get lost in a used bookstore, wholly divorced from its original context. I often think about this dimension of the process and what happens when I leave it alone. My parents are antique dealers/collectors, and so growing up, there was this temporal weight to everything around me. I realize this is kind of dramatic, but a question I frequently ask myself is: “If I die and this work is at my funeral, what would it mean?” With curators, I just want them to use the work as they see fit. It’s important to me that there’s a kind of structural openness to it that allows it to adapt to different contexts. I want it to be useful. Unfortunately, there’s a set of assumptions that’s often brought to the table that’s hard for some to unsee. A kind of default mode of presentation that may limit things from the start. That’s the portability problem: these works aren’t paintings; they can’t simply be picked up and moved into a room. The work, as I see it, is more nebulous than what’s immediately visible on your screen and can transform, sometimes dramatically, depending on its environment. When you make something online, it can be very intimate: you’re already in their home, their bed, their pocket. You can’t just drag that directly out into broad daylight.

Language appears as a central character in much of your work. What draws you so strongly to words?

I studied sculpture, actually, and it wasn’t really until I started to take programming seriously as a practice that language began to figure more prominently in what I was doing. It was never really intentional, just a natural result of working in a particular way. Everything you work with has a grain or natural tendency that inevitably shapes the final result, and with programming, text is readily available and easily manipulated. There’s so much of it, and you’re always dealing with it in the aggregate; databases, corpora, etc. And the thing that becomes apparent is how rare meaning is in the sea of all this; that the origin of meaning is always elsewhere, deferred and multiple. The problems you face start to look a lot like sculptural concerns: text’s mass and volume, its material agency, its relation to the body. These are the problems that keep me interested.

The way you remix letters and words sometimes recalls the cut-up method used by William S. Burroughs. Is there a connection to the subconscious in your work, or is everything you digitally manipulate shaped by a structured algorithmic logic?

I’m not super familiar with Burroughs, though that’s a good reference. A lot of my thinking about text comes out of Robert Smithson… the way he treated words as tangible, stackable, stratifiable “stuff.” His preoccupation with “printed matter” — less about the subconscious and more about text as a thing-in-the-world; the matter-of-factness of it. I’ve noticed that I tend to treat text’s structural qualities as distinct from meaning. Sometimes, for me, meaning operates in parallel or in addition to how one would typically parse something. Like, the structural manipulation or arrangement that I do acts to construct meaning in one particular kind of way, while the semantic content operates in a distinct register and is almost fungible.

Your works in the exhibition Self-Titled (2023) seem to propose a new way of reading and interpreting images, running parallel to how we read words. They feel emblematic of the times we live in. Has that relationship with language become fractured? Do you think language is ultimately a failing system?

I have a three-year-old daughter, and so watching her acquire language, learn to be in the world… you wind up thinking a lot about their sensory experience as they grow, trying to see the world through their eyes. They’re building up models for understanding the world, and you get to see them be in these moments before those models have completely taken hold. Soon after she was born, I started to build a system to show her arrangements of colors and language. But it began to do something exciting: the relationship between text and the sensation it invokes collapses onto a single plane. It slows down the parsing that one does to extract meaning from sentences. You’re immediately made aware of exactly how you’re looking at something and the distinction between those two modes of cognition by their proximity and relative complexities. That gap between language and sensation or ‘truth’ is a space I continually try to work within. It seems to me that there’s a shift happening, wherein that gap is beginning to narrow. With various AI models, text can now immediately summon external sensation directly, in a tight feedback loop. Venkatesh Rao calls AI a ludic technology. Our relationship with text shifts from producing artifacts to steering an ecology of responses. This itself is something akin to parenting. We may be rediscovering a latent ability within text. Carefully arranged tables of symbols conjure an intelligence… This is not a new idea.

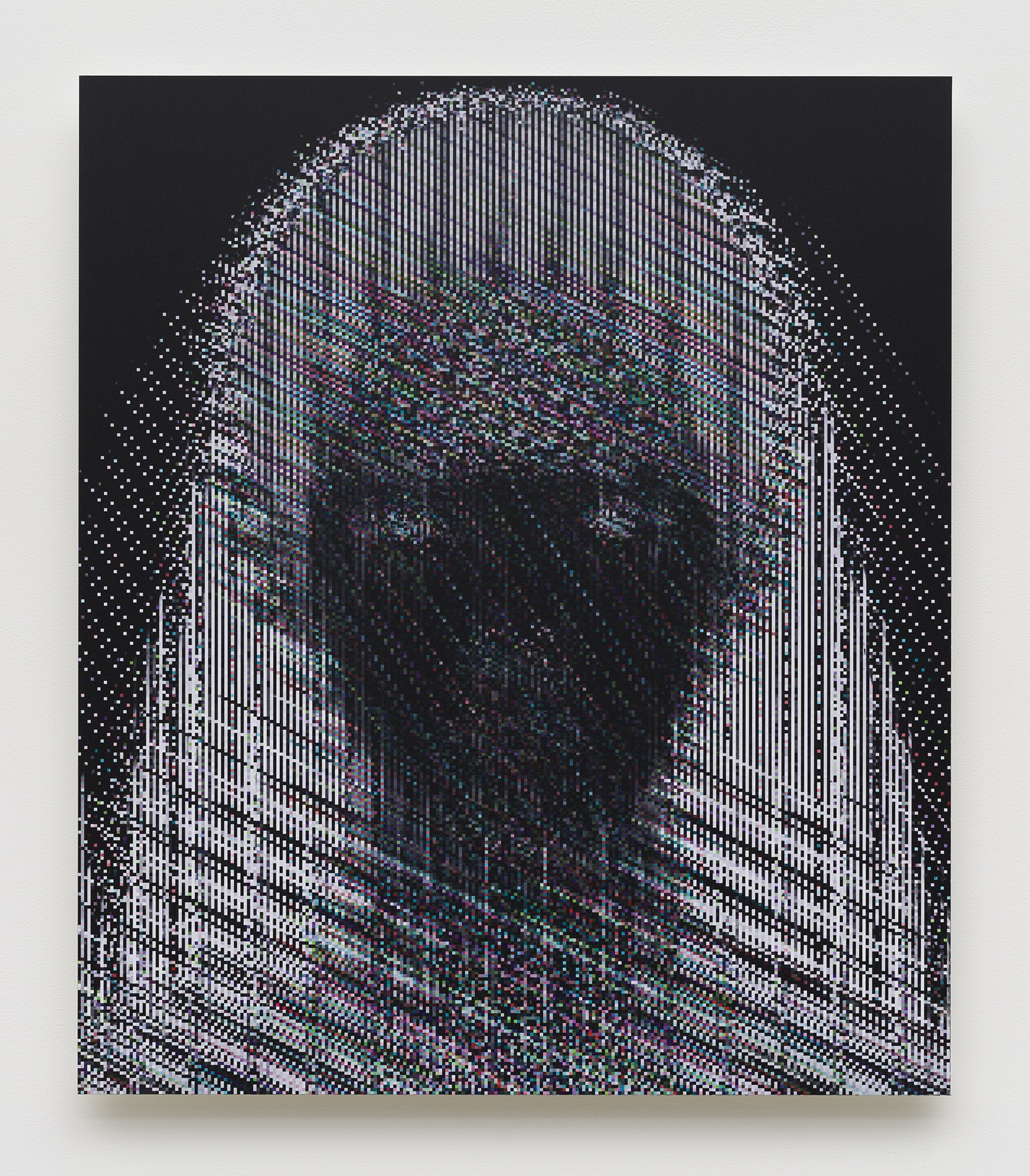

Your UV cured ink on alu-dibond prints are composed of small squares resembling pixels or RGB LEDs. They evoke both screen-based light and Impressionist colour theory. Were you looking to any particular artists as points of reference? They also feature pretty unusual titles: which is the mental algorithm that guides you in their creation?

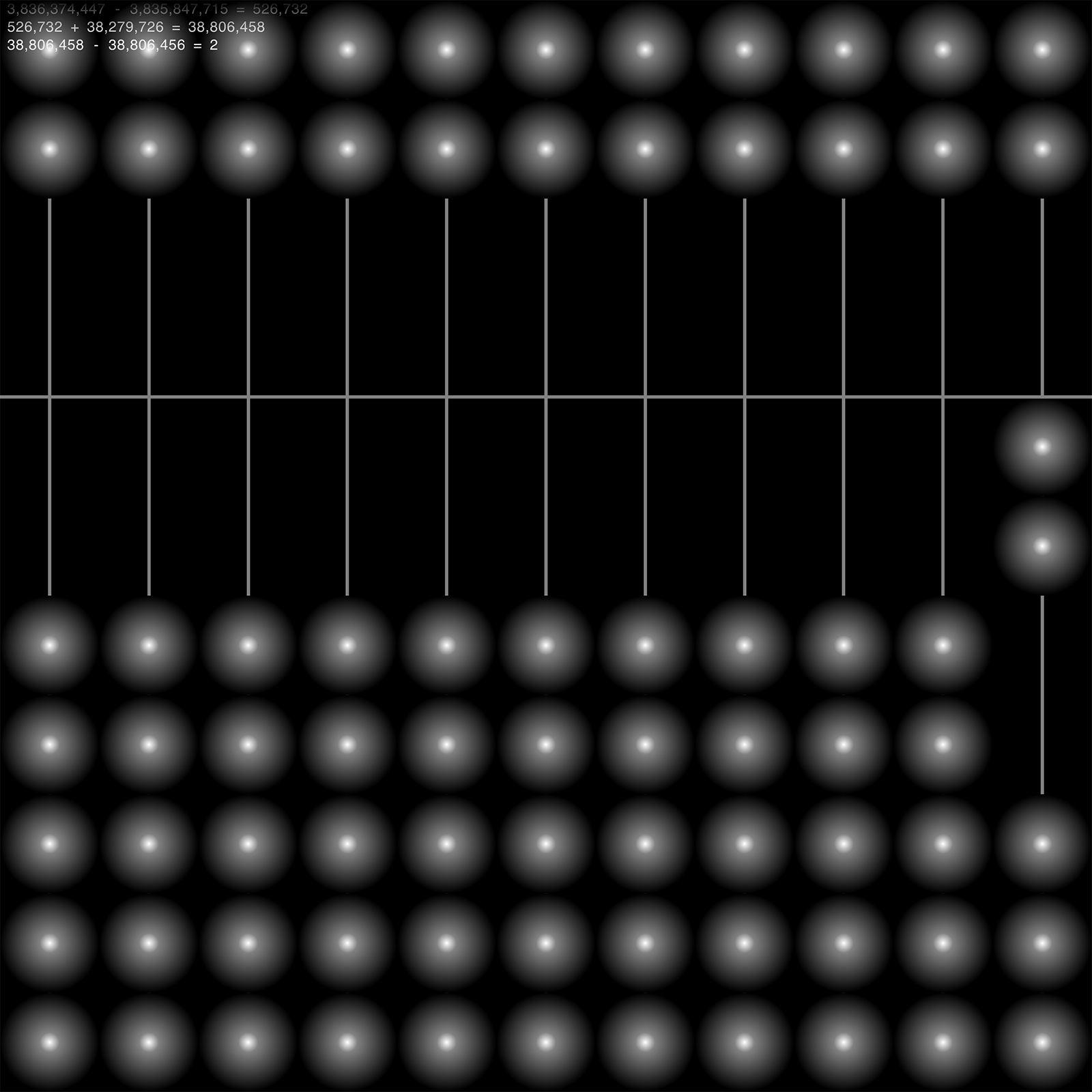

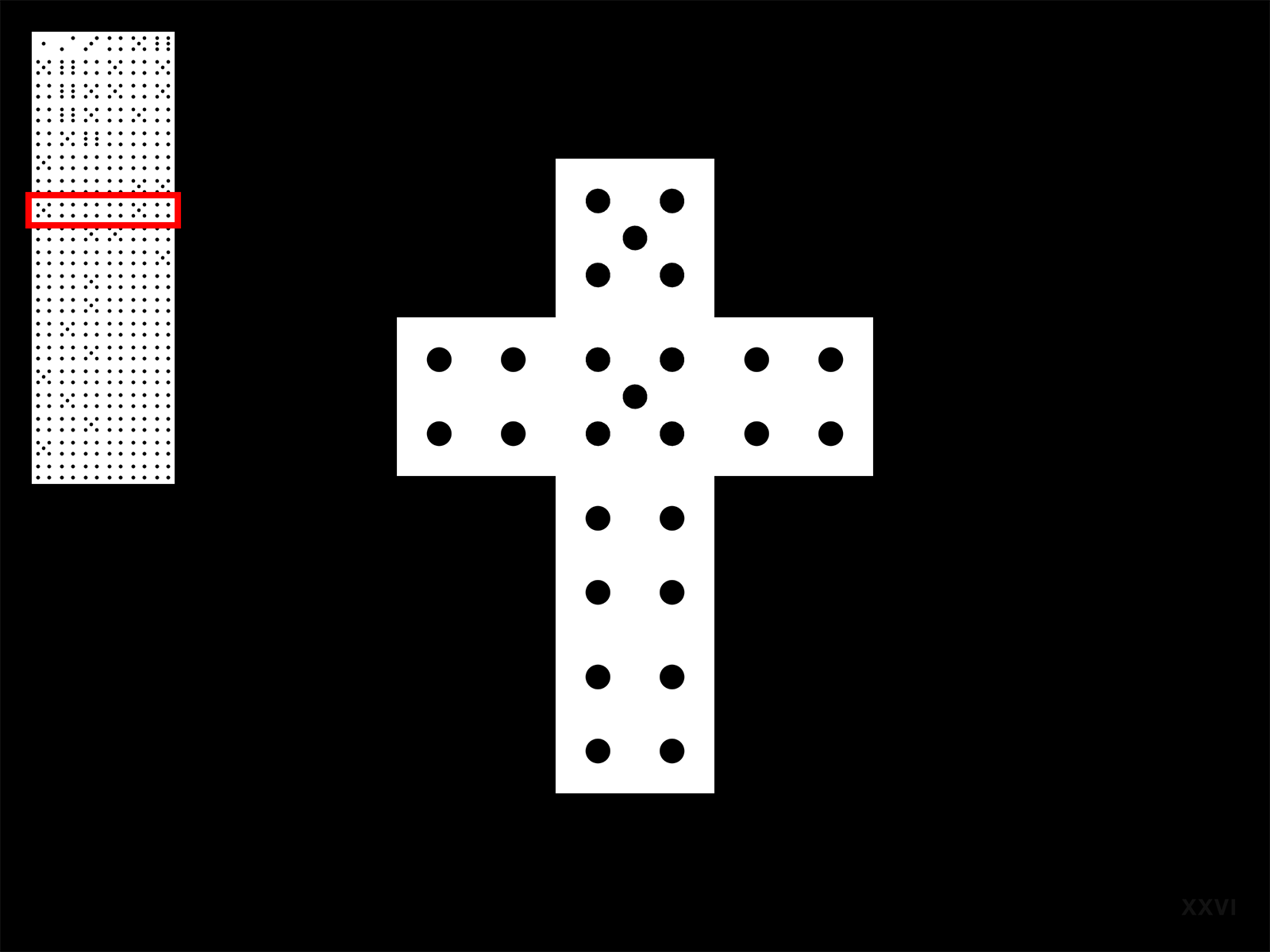

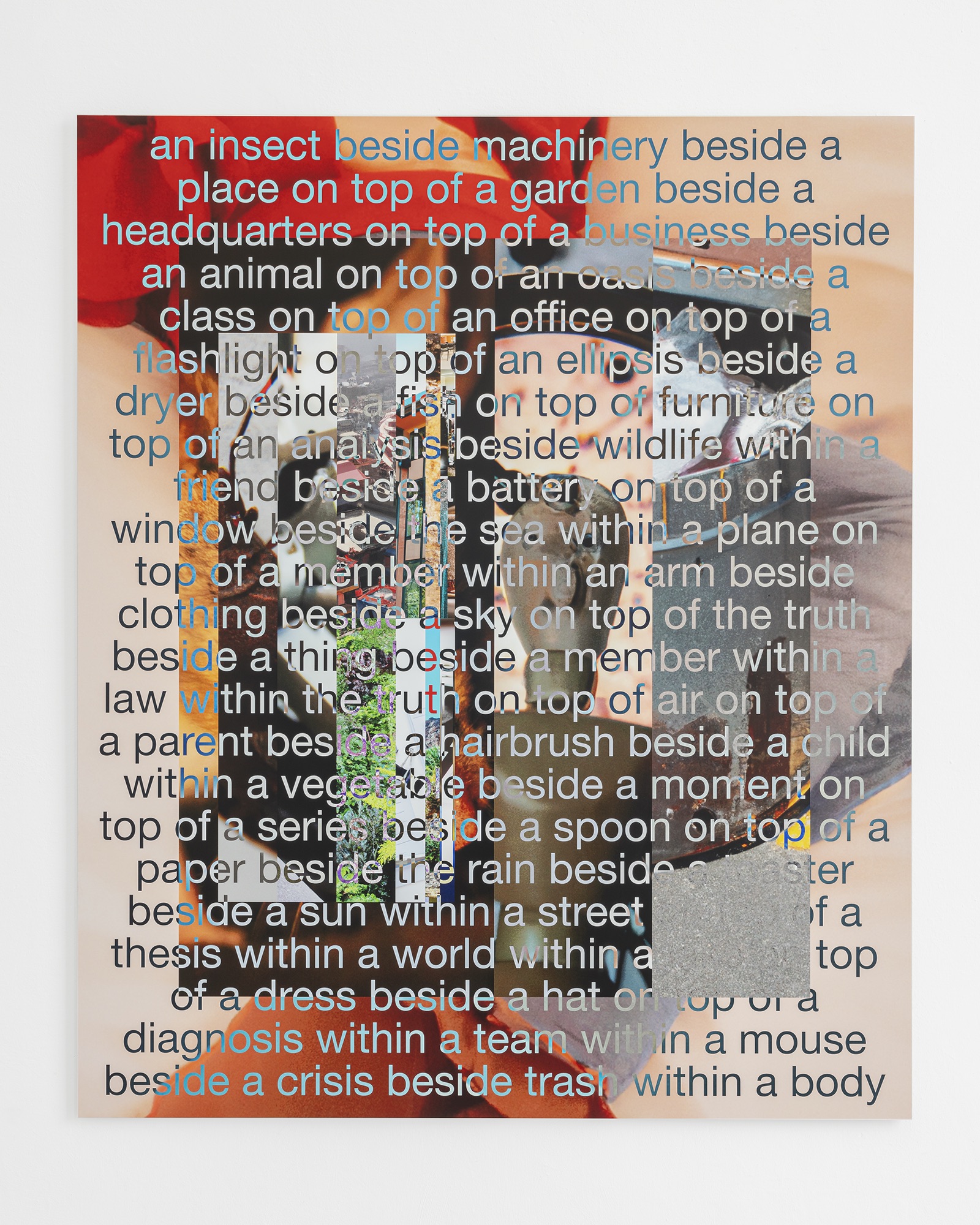

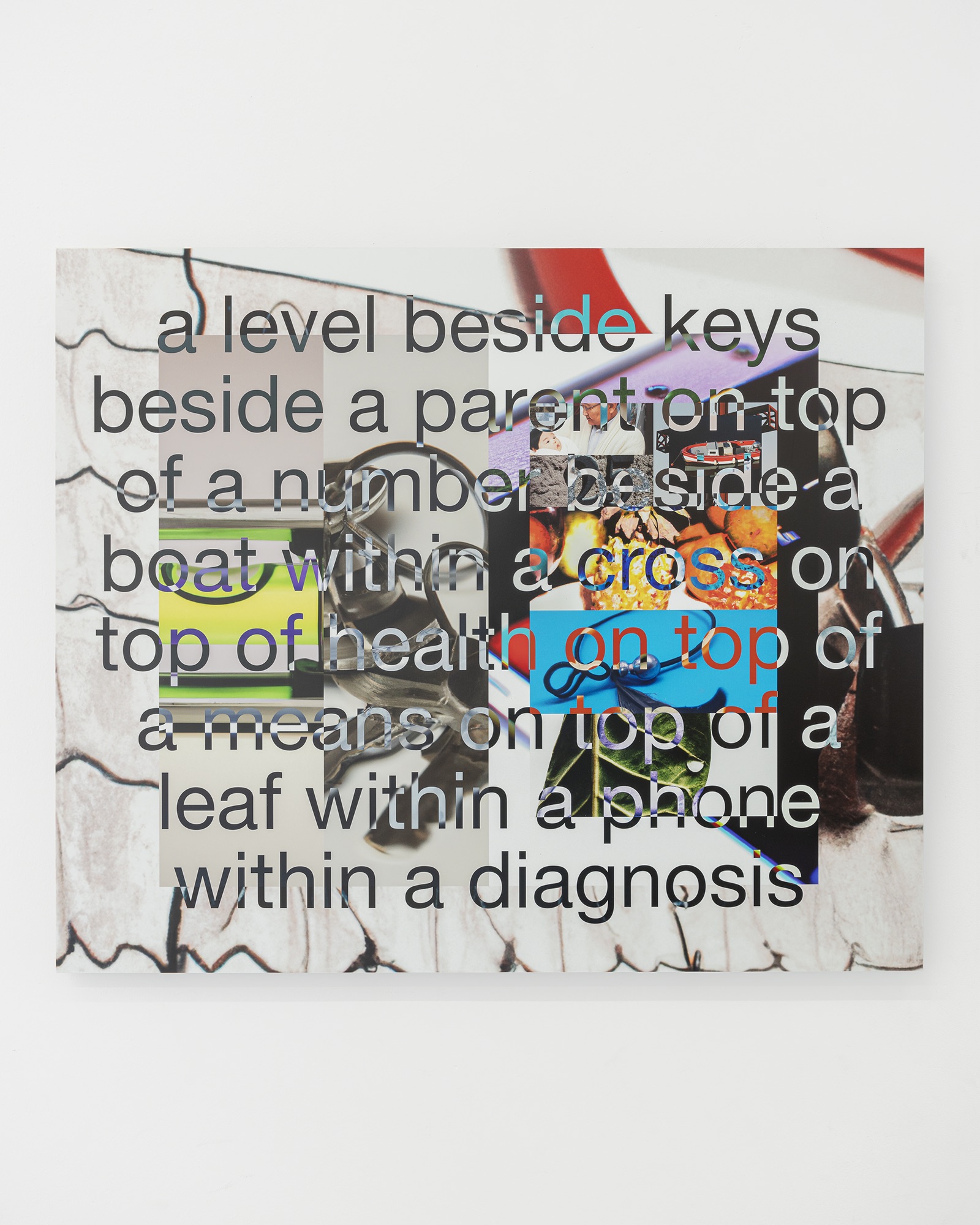

These works are composed using different populations of images. I wrote some software that operates by taking sets of images, enlarging them to cover a given dimension uniformly, cutting them into grids, then walking over that grid, taking a piece from each image in turn. The result is a composite of everything in simultaneity without any changes in opacity. You’re left with a kind of framework of each image used, punctuated with holes which are then filled by the other images. The individual pieces aren’t pixels but are actually small photographic fragments. They evolved out of some older work that was a similar process, but more focused on color. At the time, I was thinking about early experiments in additive color photography. Dufaycolor, Joly color screen, etc. These are processes that involve ‘grains’ of color that optically mix. There’s some interesting territory here before the photography’s rough edges were smoothed over, coincident with the realization that color could be encoded spatially, which was happening at the same time as the development of Impressionism. In parallel, I was working with a method I devised for interlacing fragments of text with one another to create single-word poems… trying to form a single unique ‘word’ that would serve as a stand-in for an entire text… As if a key. The titles use that process directly: Write the words in a row‑aligned grid padded with spaces, then read the characters column‑by‑column from left to right and top to bottom to form the new composite word. It mirrors what’s happening in the images, but on a different axis.

A work of yours that can’t be experienced on the screen, My Attraction May Fade, But I Will Not, is composed only of light and fog. What compelled you to move away from the logic of strips of code and enter this equally immaterial dimension?

In that particular instance, it was a direct response to the somewhat unique constraints of the exhibition space in which it was first shown. Most of the space of that gallery was a volume that couldn’t be entered but was visible from a street-level storefront window. The floor of the space was removed, so you peer down into what was once a basement from the sidewalk. While most of my work tends to take on some two-dimensional form, what I’m actually most interested in is the physical act of looking/observing. I guess this is my sculptural background talking. Much of the work I make is a consequence of intervening in some way with the inherently three-dimensional nature of vision. So with that particular piece, you’re walking by on this very narrow sidewalk, and you pass the full-length window. On the other side of the glass, there is no floor… So it immediately ungrounds you. I wanted to take that situation and amplify it by removing all visual reference by introducing the fog and tuning the light. It’s challenging to document because encountering that situation has a very visceral effect. To casually walk by a storefront and all of a sudden have no sense of the scale of the space right next to you. Your vision is dispersed, but there’s still this hard boundary between you and the picture plane. It felt to me like a type of figuration because it makes you hyper aware of how you’re standing in relation.

Counting Frame (2022), which won the OGR Award and became the first NFT acquired by the Fondazione per l’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea CRT, marked a pivotal moment in your career. Years later, do you still see the NFT as a necessary format for display and sale in the digital art sphere? You use sites to display and give life to your artworks: are there any other exhibitory modes that you’re experimenting with?

Although I appreciate how they’ve increased the surface area of people interested in digital work, ultimately, I’m not so interested in the kinds of transactions that NFTs encourage. The way I typically structure sales of digital works is more about recognizing something that is sort of the opposite of what I think NFTs try to engender, that is, that most digital works are not objects. One of the benefits for me of working digitally is its inherent mutability. And while, of course, there are ways around this with NFTs, tools always have tendencies. The immutability of the blockchain is something I’d prefer to avoid. This is that same portability problem: this illusion that the work is portable, across time and across markets, and this really isn’t the case. I’ve frequently gone back and altered pieces that are “done,” often completely recreating them. And whenever I do sell this type of work, it’s important to me that the collector realizes what they are buying: a relationship rather than an object. Practically, the thing being sold is a contract on my future labor to maintain some system into the future; to ensure that the work remains accessible over time, but also a recognition that the work has a somewhat fluid solution space of realizations. A singular answer to the question: “What is the material substrate of this work?” has more than one acceptable answer. And when one buys the work, there’s a conversation that opens up between the collector and me. Putting things online: it’s public, and the collector relationship is perhaps an older model of patronage. It’s also difficult for me to figure out how the work will continue when I’m gone. You always find yourself at the center of the work, as its “host.” I’m less interested in a singular exhibitory mode than I am in the kind of ideal of there being a fluid continuum between ‘the studio’ and ‘published’ and back again.

What are you working on at the moment? Which codes, systems, or databases are currently informing your practice?

I’ve been really drawn to video and time-based ways of working lately. I’ve been translating that method of interlacing along a temporal axis. Right now, I’m working on a piece that takes its material from urban exploration YouTubers — so these first-person perspectives in abandoned and decaying buildings. I’m also still pushing through a strange experience that is shaping my work and thinking in ways that are hard to articulate right now. Late last year, I had a severe injury to my dominant hand. It left me one-handed for a few months, and I’m still recovering from significant nerve damage. For a while, I had a hard time working because it felt like part of my cognition was embedded in my hands; in the manner and speed that I typed, and the particular feedback loop that it enabled. These are things I’d expect to hear from a carpenter or a painter or a chef, but maybe not a programmer. I can’t feel most of the hand, but what’s interesting is that as the nerves regenerate, I get to experience a kind of bottom-up rebuild of what sensation is. The different dimensions of touch are coming back in other regions, dislocated from one another. For example, it seems like it’s possible to discern texture while having no sensation on one’s skin. Or that it’s possible to sense the inside of a digit independently of the outside; proprioception in isolation somehow. Most surprising is to learn of the link between our feeling of free will and our sense of touch… that there’s a kind of choreography of agency that arises out of the interactions between brain, body, and world, and that this illusion is ultimately somewhat brittle.