You don’t want to lose the coherence of your method, I would say.

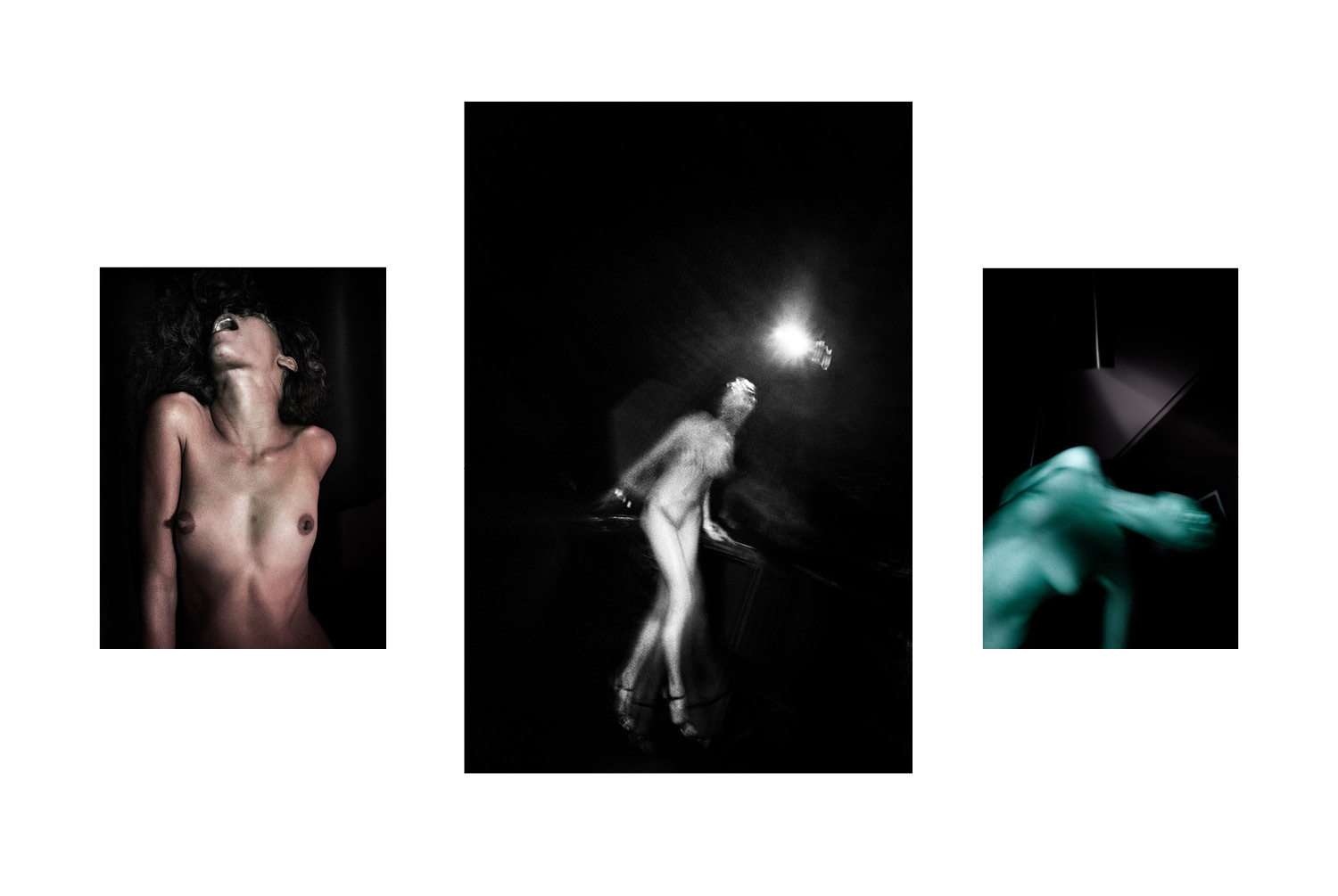

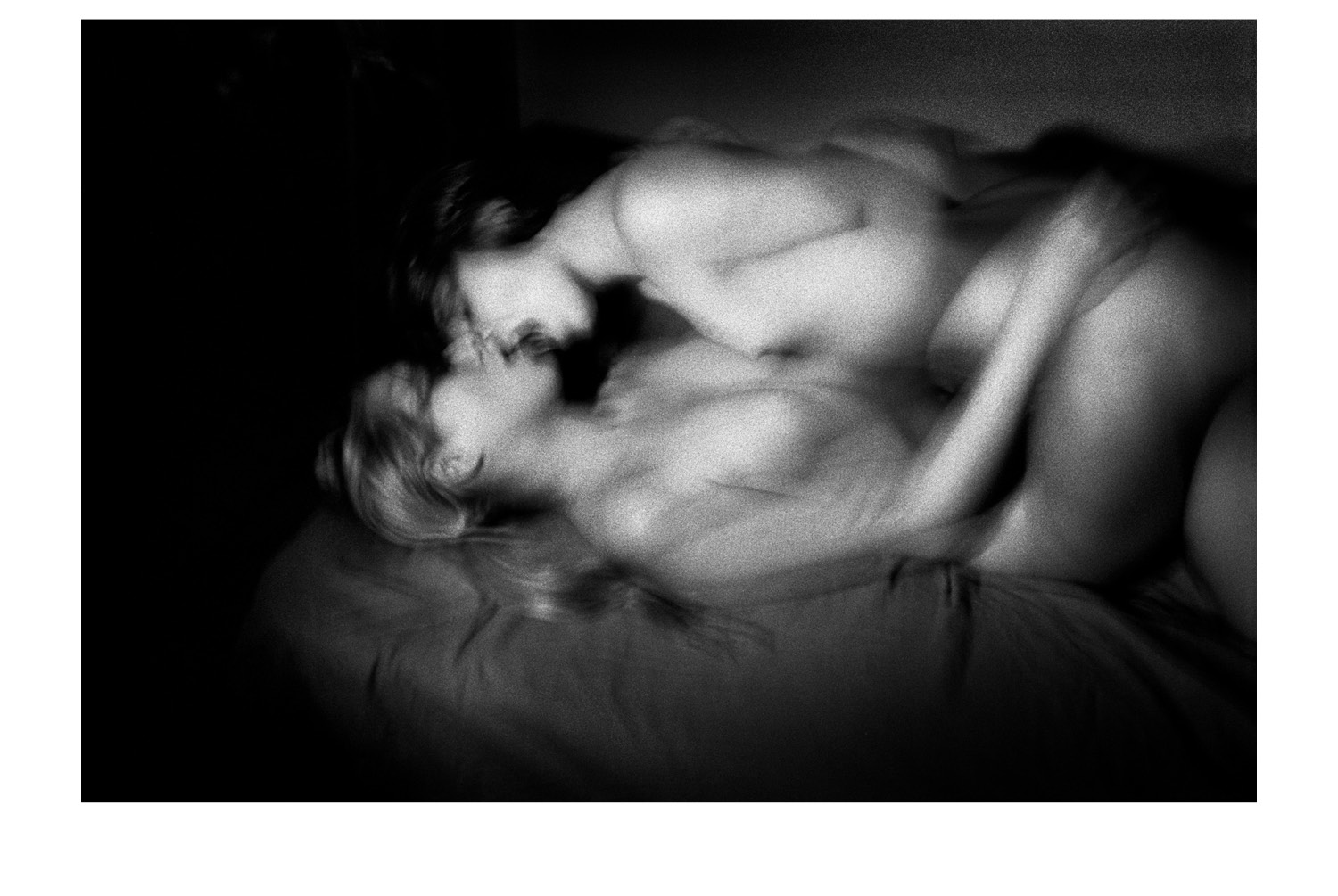

And it takes a lot of physical strength which sometimes I do not have anymore. It takes a lot of everything. Because it is a destructive process. Because it is an agonizing and isolating process. Day to day, on a personal and intimate level, on a familial level, on the social and professional levels. I am struggling through the difficult relationships I have with the people I photograph or do not photograph, with the ones who try to help me or to neutralize me. It is damaging. It is intense. It is violent. And I must focus on the work, even though I lack the means and lose my strength. I sacrifice as little time and energy with others so that I can keep going. It is difficult economically, it is difficult politically, and I feel helpless, or hopeless, in many ways. But that is all I have. I fight for principles. I fight for morals. I fight for a kind of purity that I will not compromise to the comfort of the spectators, critics or other economical actors of the artistic scene.

And I know you have just said that you do not care about the final perception of your work, but I feel it is important to ask you. Looking at the times we are going through, with societies becoming more conservative, with the rampant ascension of fascism all over the world, how will your work evolve in this scenario?

I have no illusion about my capacity to be efficient in any way. I am too isolated. I guess the only thing I could hope for, the only thing I would wish for, is to play the part of those insects what Pasolini wrote about…

Yes, “La scomparsa delle lucciole”.

Exactly. Maybe the memory of the work will remain as a possible alternative path, as a valid political or existential strategy for isolated beings looking for ways to resist the economic violence and cultural lie. That’s it. I do not pretend to be some sort of militant or warrior. And my gestures are purely symbolic in some way.

During your 147-day residency at the Centre Pompidou, you dissected and catalogued four decades of your own work under public observation. How did that act of self-examination change once it became a public performance? Did the exposure of your archive alter your sense of intimacy and vulnerability?

Yes. During those months of presence inside the museum, the mental and physical pressure were extremely violent. The public dimension of the performance, if I call it that way, was overwhelming. Communicating constantly with the visitors, answering questions, sharing an intimate work process with so many people hour after hour, day after day, while building the archive was an impossible task. But that was the point. It was exhausting. And it was beautiful too. Allowing a flow of person with very different intentions and reasons to intrude and enter a private space. It was intense and sterile sometimes. Destructive also when the protocol diminished my capacity to work. I was meant to focus on what I was doing, and the public exposure made everything more complex. But I function well in extreme contexts. And building this structure, this machine was a desperate act. From the very start, I had no interest in exhibiting. I only needed to build an archive, to save what could still be saved from those years of nomadic life. I had to search and recover whatever could trace those thirty years of photography. The physical dimension of this construction was essential. The archive will not be exhaustive, but it had to exist. And beyond generating new images, I am struggling these days to build a space which will integrate this huge archival structure. The cube I built at the Pompidou will survive in the place that will become a strategic and symbolic environment, and a workplace. Maybe I will have a few more years to continue working on that. So yes, this was also an artistic and strategic gesture. Maybe because I no longer have the capacity to produce that I used to have. The body is damaged. And I need to work to, financially, keep myself able to work. Teaching, selling prints from time to time, allow me, with difficulties, to take more photographs. It is a continuous struggle, and I must admit the limits of my practice.

I feel this is a universal struggle in the creative domain, even if I hate the word creative. You once sent thousands of undeveloped rolls of film to the Niépce Museum, refusing to see them yourself, as a statement about the importance of creating regardless of the result. Have you ever felt that your life has become more important than your photography? Thinking of those photographs, is it important that your legacy survives? Is this something you even think about?

You know, I was never able to find the point of perfect balance where life and creation would be equal. It has always been a continuous and frustrating attempt to delimitate an impossible space. At certain moments I was still too much of a photographer, and at other moments I was too involved in life itself to care about photography. During the last thirty years I have moved back and forth between thinking too much as an artist and thinking too much as an addict of all sorts. Both extremes probably damaged the work in many ways. Yet in this movement, in this oscillation, I found a form of balance and serenity. This endless quest allowed me to live at heights and depths whose possibility I didn’t suspect. I feel privileged and I am grateful to life I was able to live through all this. I know there is no possible way I could do more or better. The specificity of my position as an artist, as a human and social being is probably to have based on provoked experiences and situations, the course of my existence. The inspiration of that attempt to live in a deliberate way owe a lot to the writings or Rimbaud, Artaud, Céline, Bataille, Debord and others. I never compromised on this attempt to live my life to the height of words and ideas. I tried to live and to make a point. With old age already there, I cannot help but look up to the void. But my concern isn’t the amount of time left, nor my lack of perspectives or expectations. I am an atheist. Darkness will eventually take me. I think of death. I think of those who left. I think of those who’ll stay behind.

I get it. It is very beautiful that you are thinking so universally. Even after this interview, I get such a clear sense that your practice is solitary, yet there is a continuous generosity coming from you and from your photography, and that is very beautiful. I just wanted to say that.

Words are only words, but it is in the small, in the wounds, in the obscure that we find possible ways to approach dimension of the tragic, of what we have in common. Let’s not neglect them.

No, that is a great thought. Thinking about pearls of wisdom like this one, when teaching young photographers, what is the lesson you find yourself repeating most to them? What do you see as their generation’s greatest obstacle?

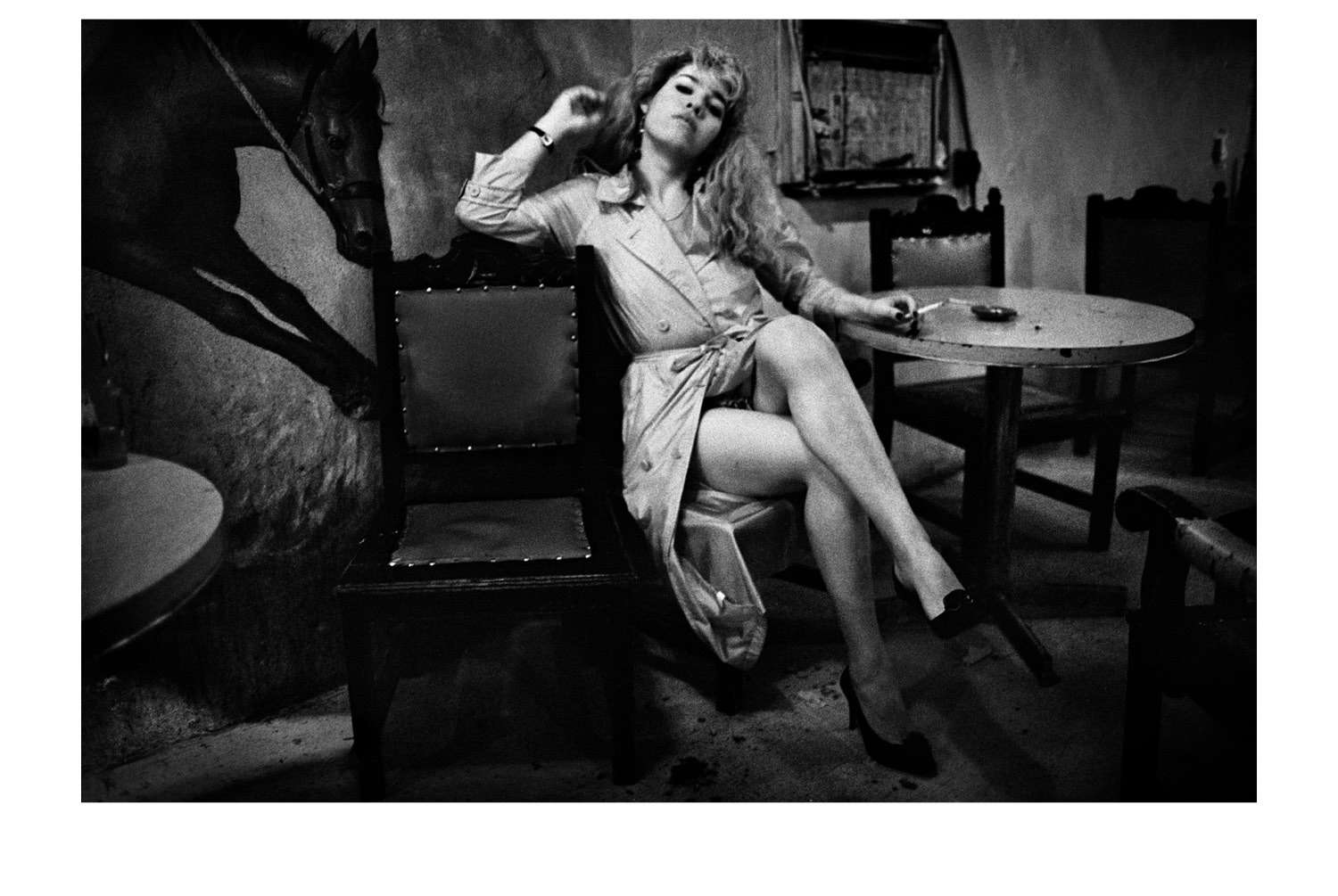

I am not a teacher, but someone who communicates and exchanges with younger, or less experimented photographers, and I go to great lengths to make sure they do not become victims of the cultural lies or illusions that take place around photography, around whatever art is supposed to be. I try to make sure that they do whatever they do not only out of an aesthetic concern, but also from an intimate, physiological, political, and animal urge. I want them to understand they can make the choice not to be a consumer nor a spectator.

On this topic, do you think that photography still has the power to disturb and infect or has it become too part of this system of comfort that you’re alluding? Is there hope for you?

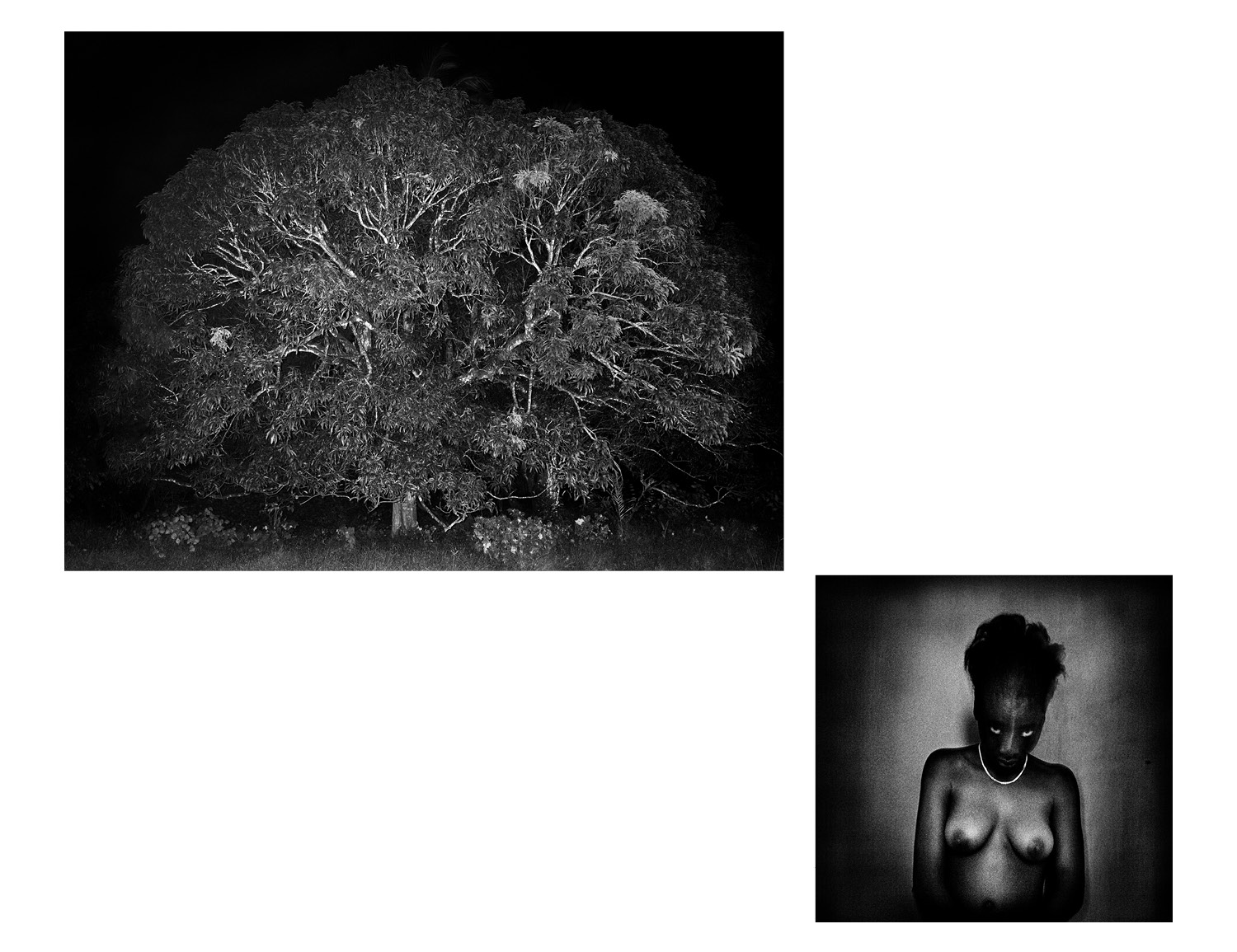

This makes my position frustrating every day. The photographic image is a tool that gives me the capacity to occasionally go where I need to go, to translate my experience of the world in something I can somehow communicate to others. And in the same time, the use of photography has never been so extended through human society. But, in the contemporary world, images are manipulated, perverted, formated, dangerous to the extent that it becomes the privileged medium of a global and totalitarian system of communication. In some way, I cannot escape this state of things. Part of the work ends up in public space, in a context that is, as a matter of fact, damaging its own purpose. It is the enemy’s territory. Every day, I reconsider my process, assess the context, redefine possible perspectives and strategies, to preserve my capacity to act and react. I am conscious of the dangers, and know my position is fragile. As soon as I have the means to assure my autonomy for a short while, I give up professional and social obligations and return to my own logics. It is not a comfortable dynamic but it is the most I can do. It is about being unapologetically yourself and using every available mean to resist the dominant powers, from within.

During our exchange of emails it was mentioning that you’re currently working on a documentary. Could give us a little bit of a sneak peek regarding your most recent projects, what you’re working on?

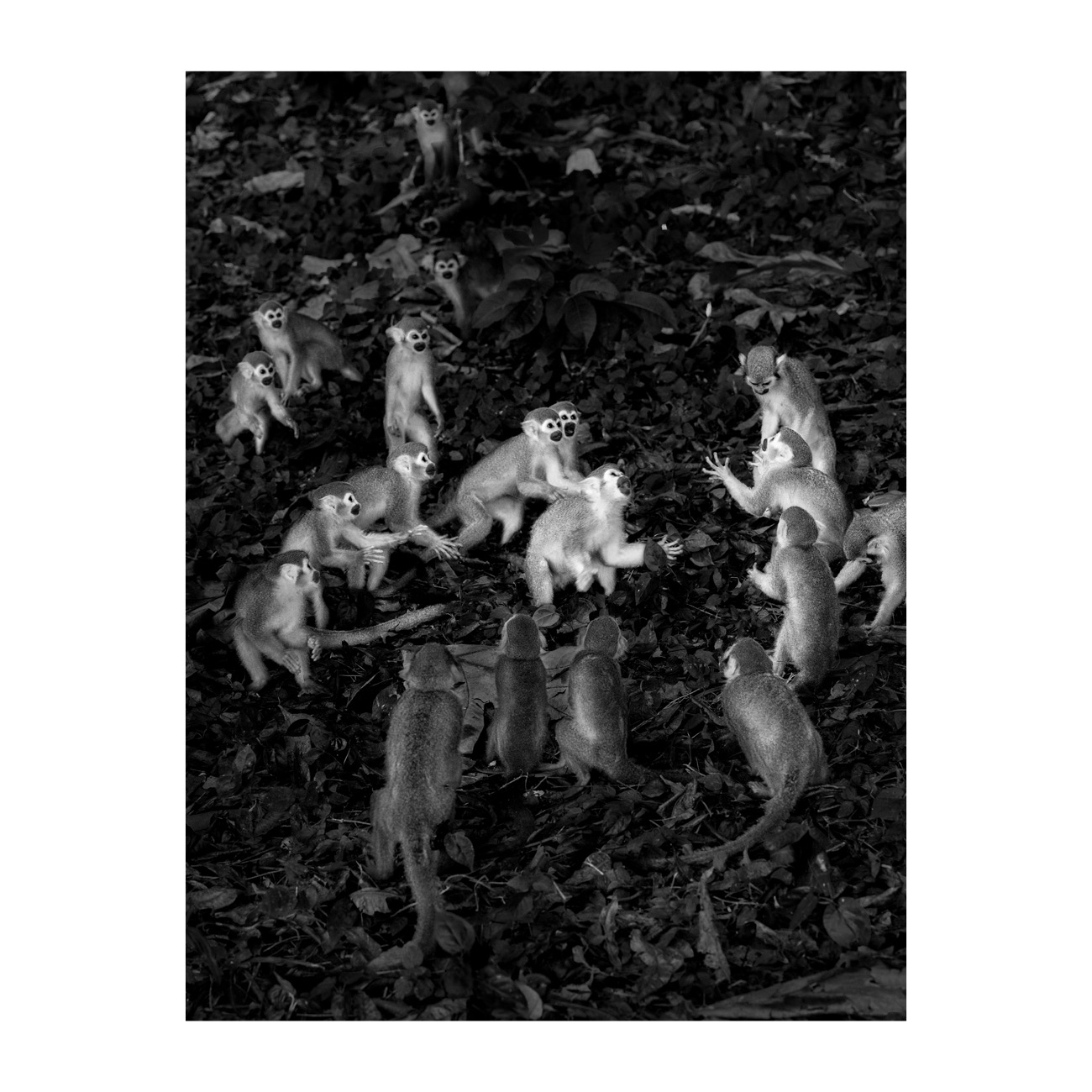

The film mentioned in my email is a long‑term documentary some people are making about my work. As for me, because my body is broken and my mind exhausted, I consider bringing the work to a close. Maybe because of the current state of things in the world, I will focus on political violence the next three or four years before putting an end to my practice. I am working in relation to found archives, drawing some kind of abstract geopolitical map of the world. It comes down to moving through time and territories, into the dark realities of human society. A few days ago, I was in Vietnam documenting the fourth generation of handicapped victims of Agent Orange, chemical used by the US Army during the war in the 70’s and still genetically transmitted, fifty years after the events.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/kittin-hacker-nasty-magazine-sq.png

869

869

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2022-03-02 12:40:002024-10-14 17:11:49Kittin & The Hacker / Electro storytelling

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/kittin-hacker-nasty-magazine-sq.png

869

869

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2022-03-02 12:40:002024-10-14 17:11:49Kittin & The Hacker / Electro storytelling