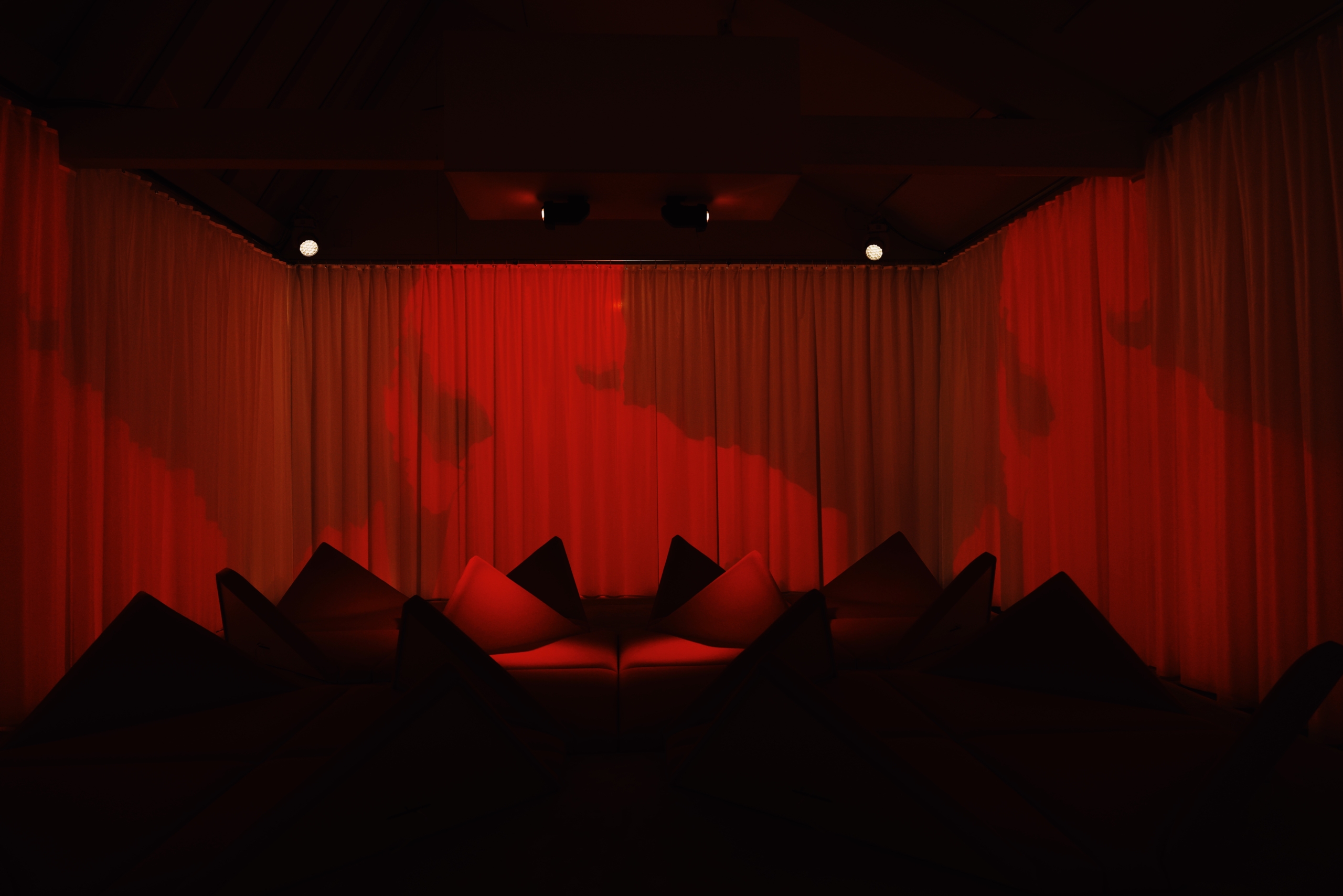

Design becomes presence, moving beyond the object to live with us and breathe with us. Benjamin Paulin carries forward Pierre Paulin’s vision by placing forms in spaces where sound and touch expand their meaning. In Saal 1 with MONOM and 4DSOUND, furniture turns into vibration, space becomes resonance, and the body enters a new way of inhabiting. The installation opens design as a living tool for memory, sensation, and transformation.

Nils Frahm at Barbican / Unwavering Devotion To Sound

Music | Spotlight

Jamie Macleod Bryden attends composer Nils Frahm’ s first London shows in over five years. At the Barbican.