In a previous interview you’ve defined photography as autonomous, but video as an extension of it. If the medium is the message, in which way do you select moving or still images when conceiving a piece? How do you distinguish between what stands alone and what evolves from previous forms of expression?

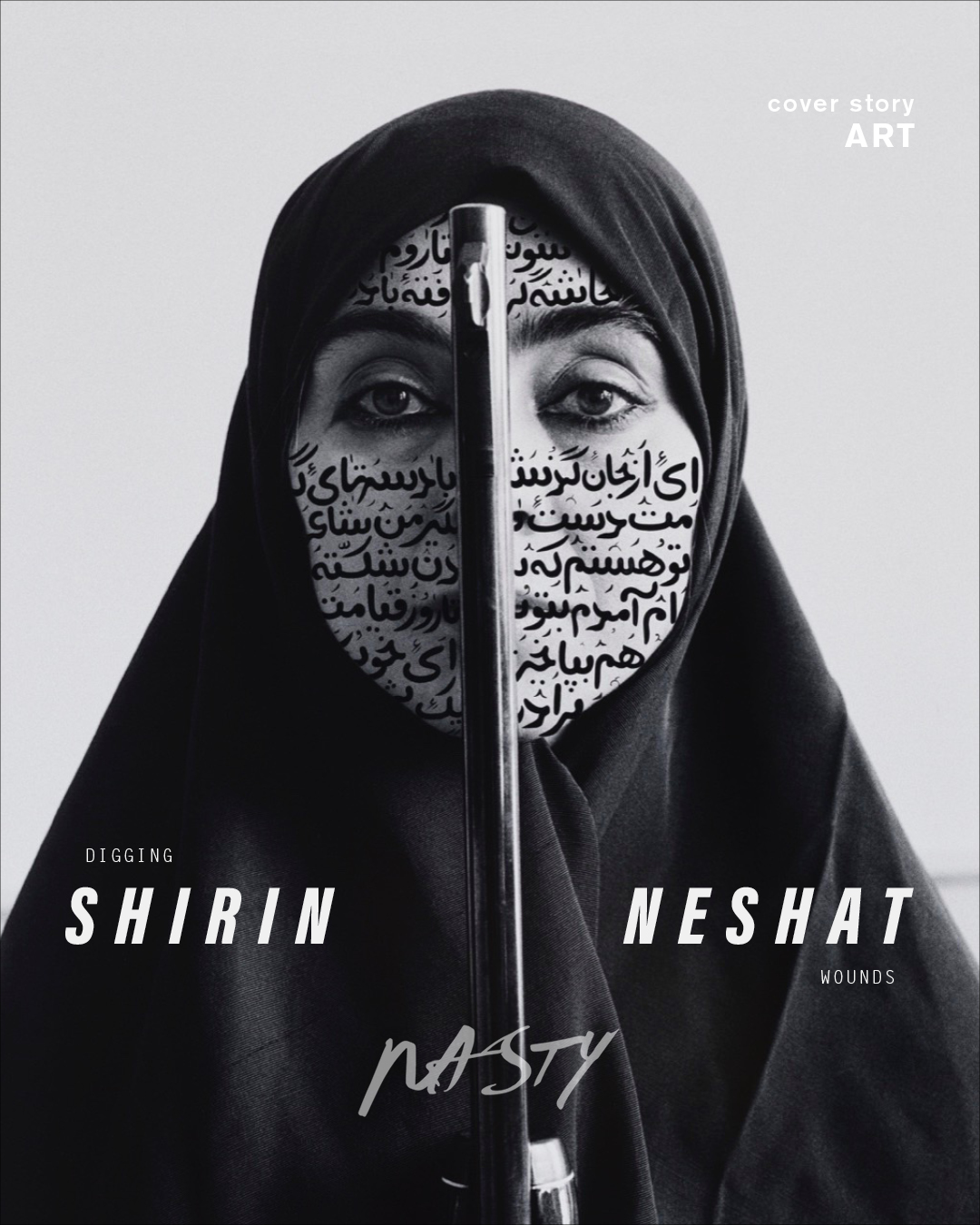

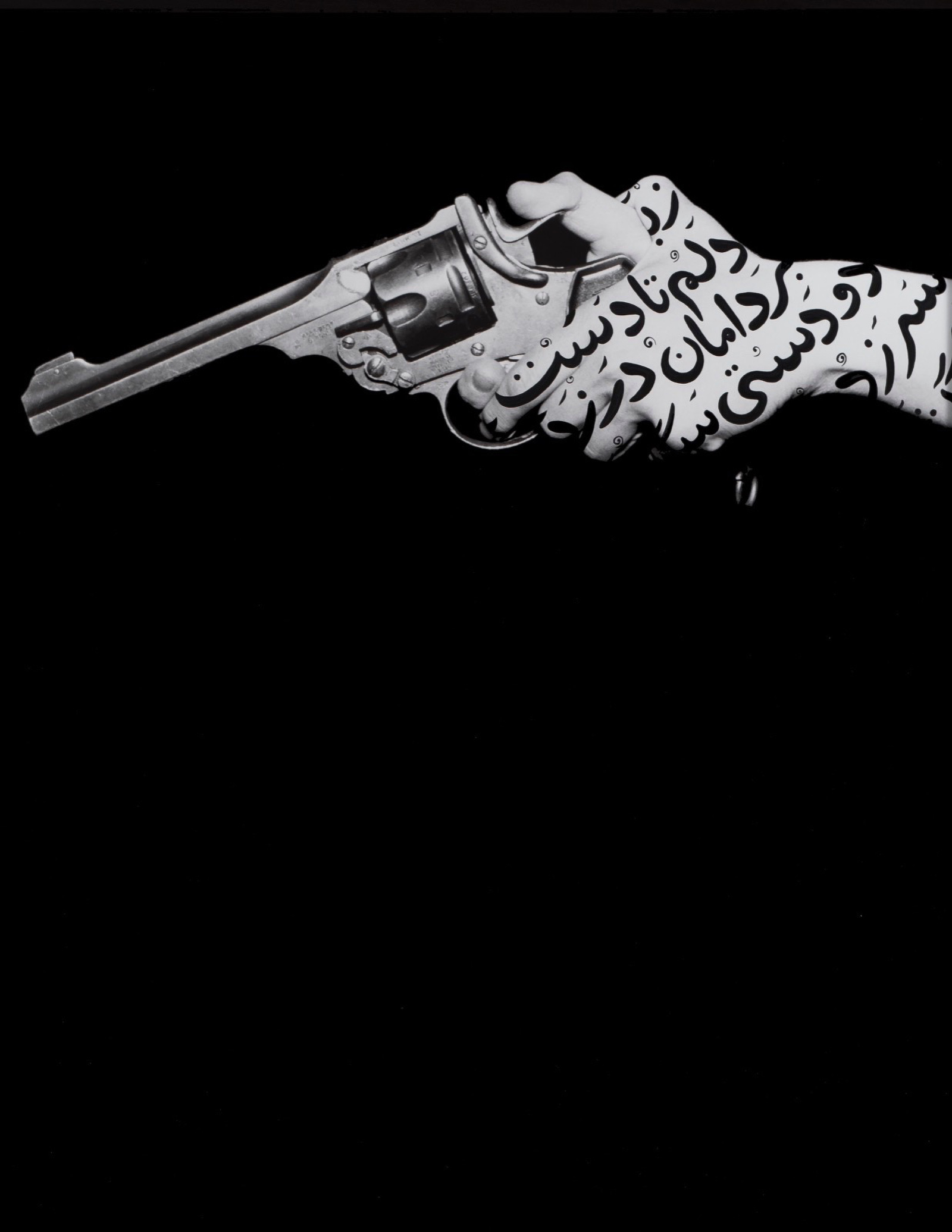

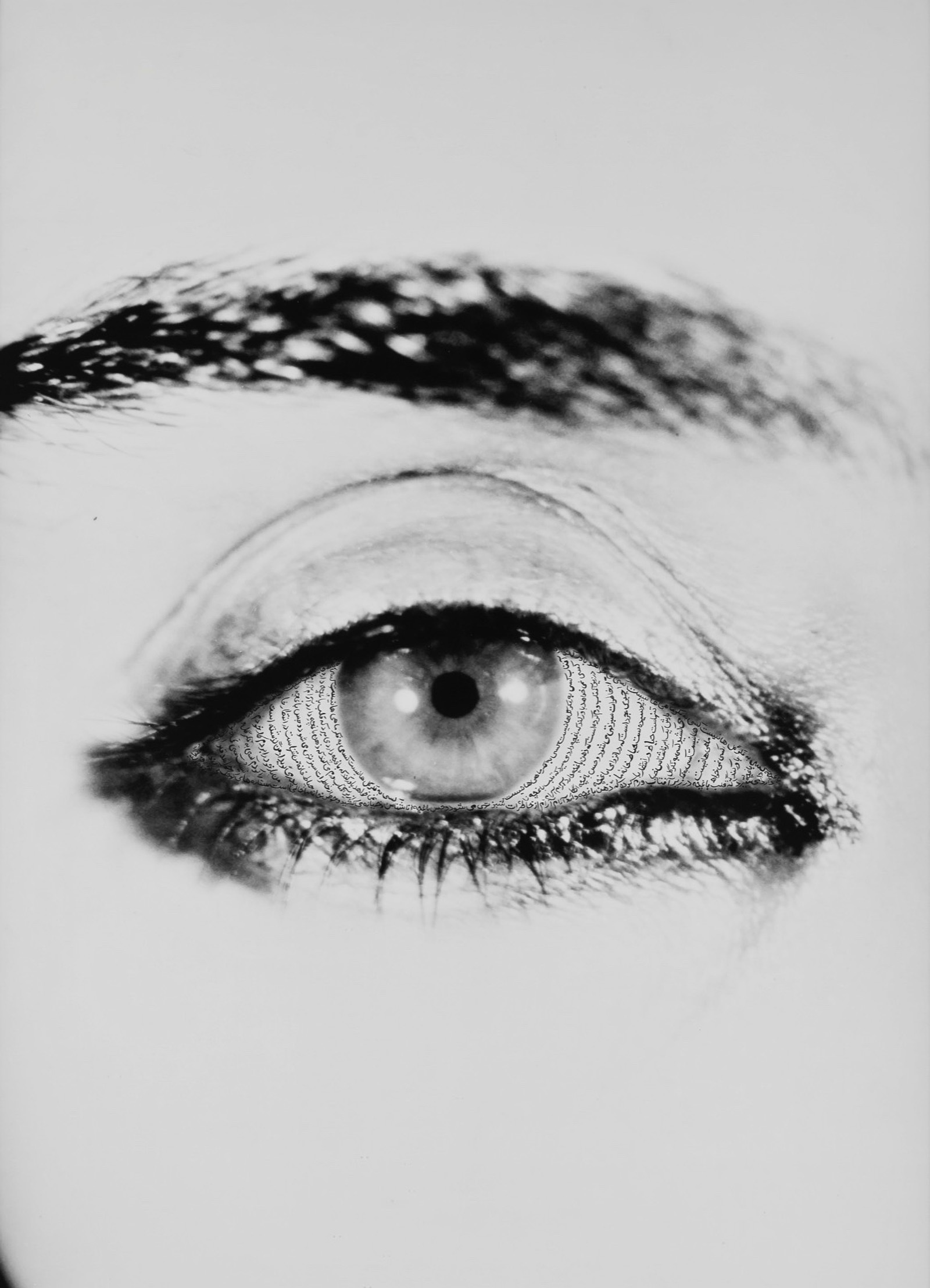

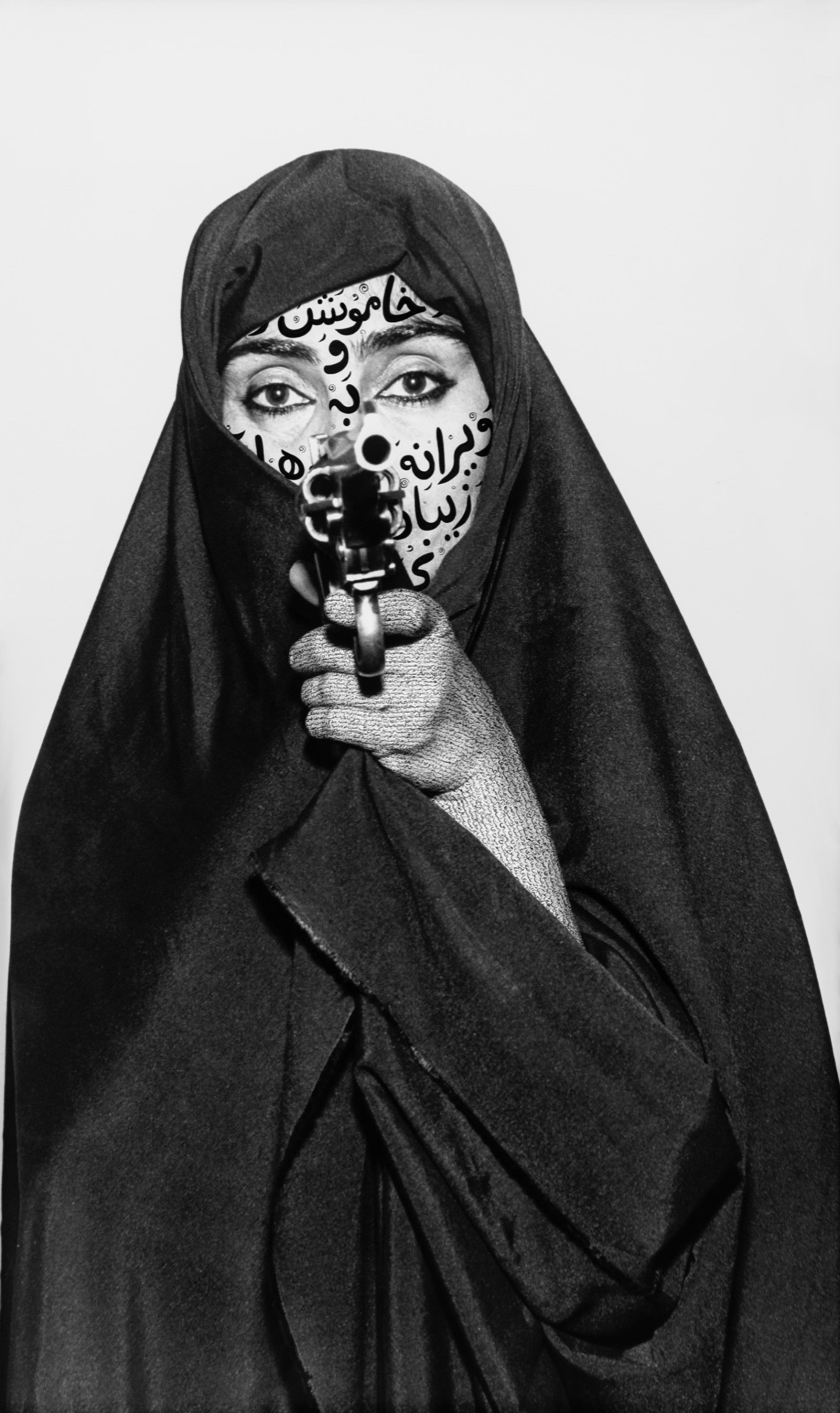

Photography is about making images where one hopes a single frame can tell an entire story. That is very difficult to achieve these days, especially with the presence of social media. Video, on the other hand, is about storytelling through a sequence of images. With video you have the help of music, choreography, production design, camera movement, performance, time, even the landscape, all of which help you draw the audience into the narrative. With photography, at least in my work, there is no landscape. You are only dealing with the human body, because I only work with portraiture. The idea is that through the simplicity of body language on the face, hands, arms, feet, lip, eye, you must convey an entire story. That has to be powerful enough to hold the viewer’s attention. For me personally, photography demands a very different type of attention and language from the artist. I actually think it is more difficult to make a strong photograph than a video, because you have far fewer tools. Often it all comes down to a person’s gaze or the way the body is held. There is also the matter of attention span. With a video, you can keep people in a room for ten minutes, you can seduced them with music, sound, choreography and camera movement. With a photograph, viewers often just pass by very quickly. So how do you captivate them with a single frozen moment? I find both mediums extremely challenging, but I believe photography is the more difficult one, especially today when everyone with an iPhone is producing striking images.

In your work, the body is a political, poetic, and spiritual presence. Borrowing the term Body of Evidence from your latest exhibition at PAC in Milan, in which way can the body become the ultimate proof, the evidence of resistance? What does it entail to put it on the line?

Yeah, I mean, of course I come from Iran, and for me it has always been striking how the female body is so heavily loaded with meaning, a political space for religious and ideological rhetoric. The female body is obviously a sexual object, therefore considered a point of shame. It has always been such a complex issue in my culture. I think Iranian women have lived with this paradox across generations: the body can be a point of empowerment, but also an object of violence and oppression. That is why, when we were searching for a title for the exhibition, I chose Body of Evidence. So many of the works being shown at PAC featured the female body as the central focus for feminist but also political discourse both in photographic and video works, each in their own way. Best example is the recent Woman, Life, Freedom movement, it was provoked by the murder of an innocent woman, Mahsa Amini for slight showing of her hair. This incredibly unjust force by the regime unleashed a euphoric and powerful revolution across the country by the women of Iran.

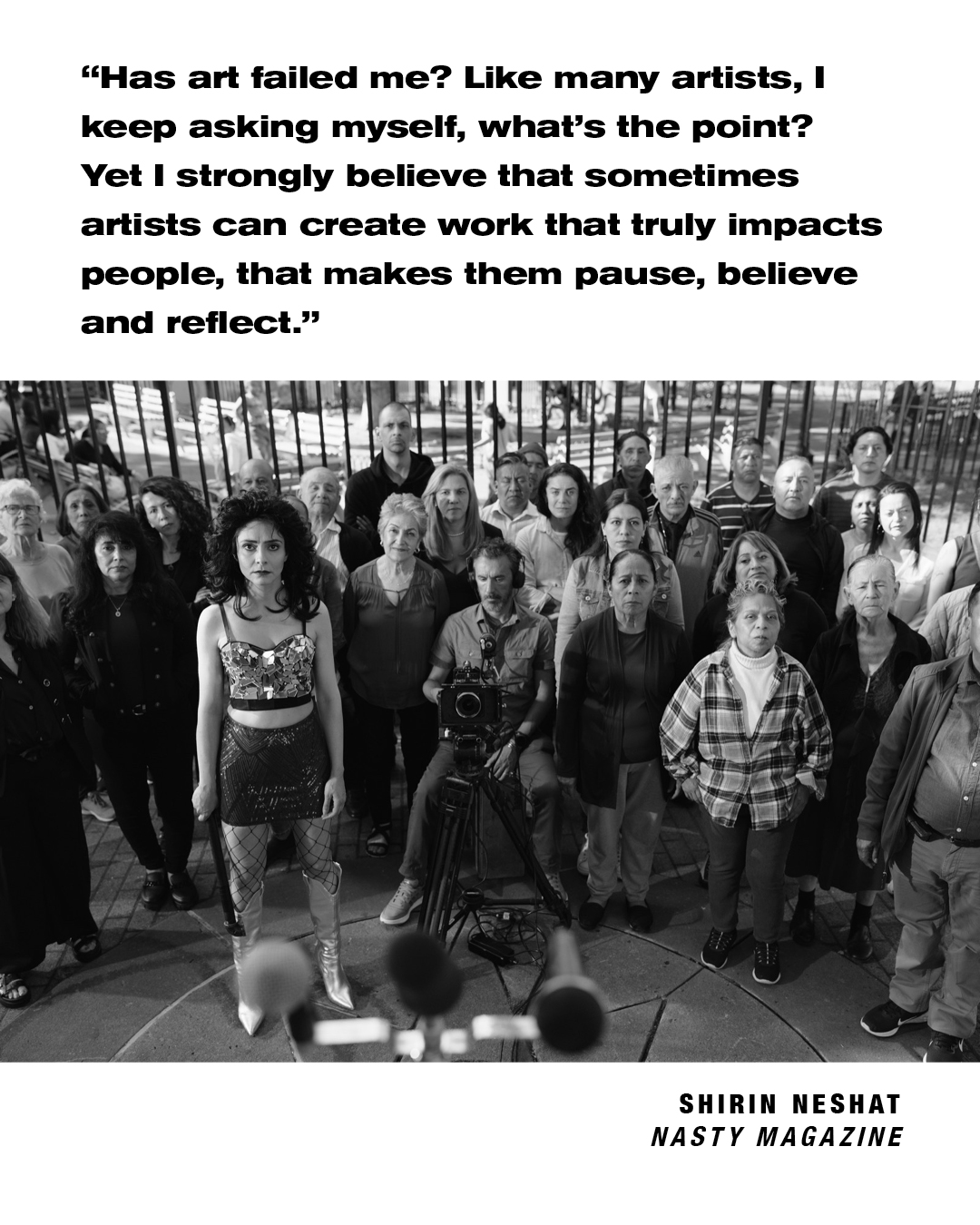

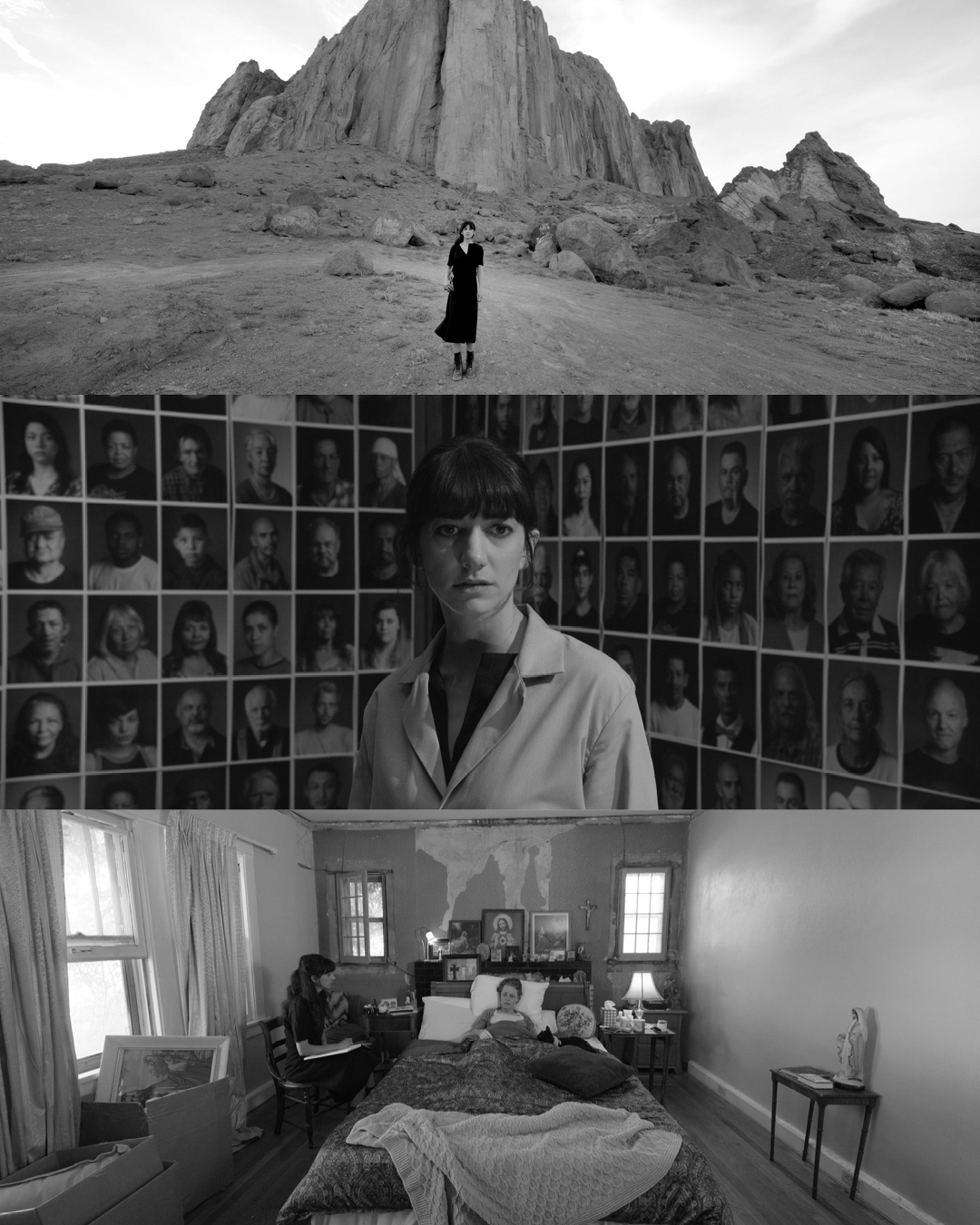

Whether inside the focal point of your camera or photographic lens, women remain your privileged subject. In two-channel movie The Fury (2023) you gave voice to an Iranian woman victim of exploitation and that couldn’t escape those ghosts from the past. Which are the womanly struggles that keep presenting in your artistic path and that are occupying also your current research?

It came out of my listening to the trial of an interrogator who had sexually exploited women in prison. That became my obsession. I kept asking myself, how does a woman ever recover from such trauma? That is the only reason I made The Fury. Through my research I also came to understand that most men and women who are sexually assaulted and raped in prison never truly recover and many commit suicide. The Fury, is a fiction about a woman who is now free in the United States but is haunted by her past and not functional in her new reality.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Conrad_Shenzhen_Grand_Ballroom_Lobby_LO-RES.jpg

1036

1600

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2024-07-06 18:14:332024-10-10 17:00:54A place for dreamers / Conrad Shenzhen

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Conrad_Shenzhen_Grand_Ballroom_Lobby_LO-RES.jpg

1036

1600

admin

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

admin2024-07-06 18:14:332024-10-10 17:00:54A place for dreamers / Conrad Shenzhen