How did you start your creative practice? What guided you into becoming an artist?

I started my studies at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna in my late 20s without knowing anything about visual art. As before, when I did a carpenter apprenticeship I was attracted by a vague romantic idea. My biggest influences are my grandmother and her love for storytelling, and my travels outside of Europe. But to become an artist, a working artist making enough to live is not at all romantic, rather a matter of perseverance and and exploration of different media while one’s ideas about the world and one’s relation to it and how this can be visualised is the constant background hum of living which also needs ignitions of enthusiasm. I’m in sympathy with what someone said that the work one would do tomorrow would be the best work one would do, that kind of enthusiasm.

Collecting and archiving seems a big part of your practice. Can you explain why it is so important for you and how it reflects conceptually on your practice?

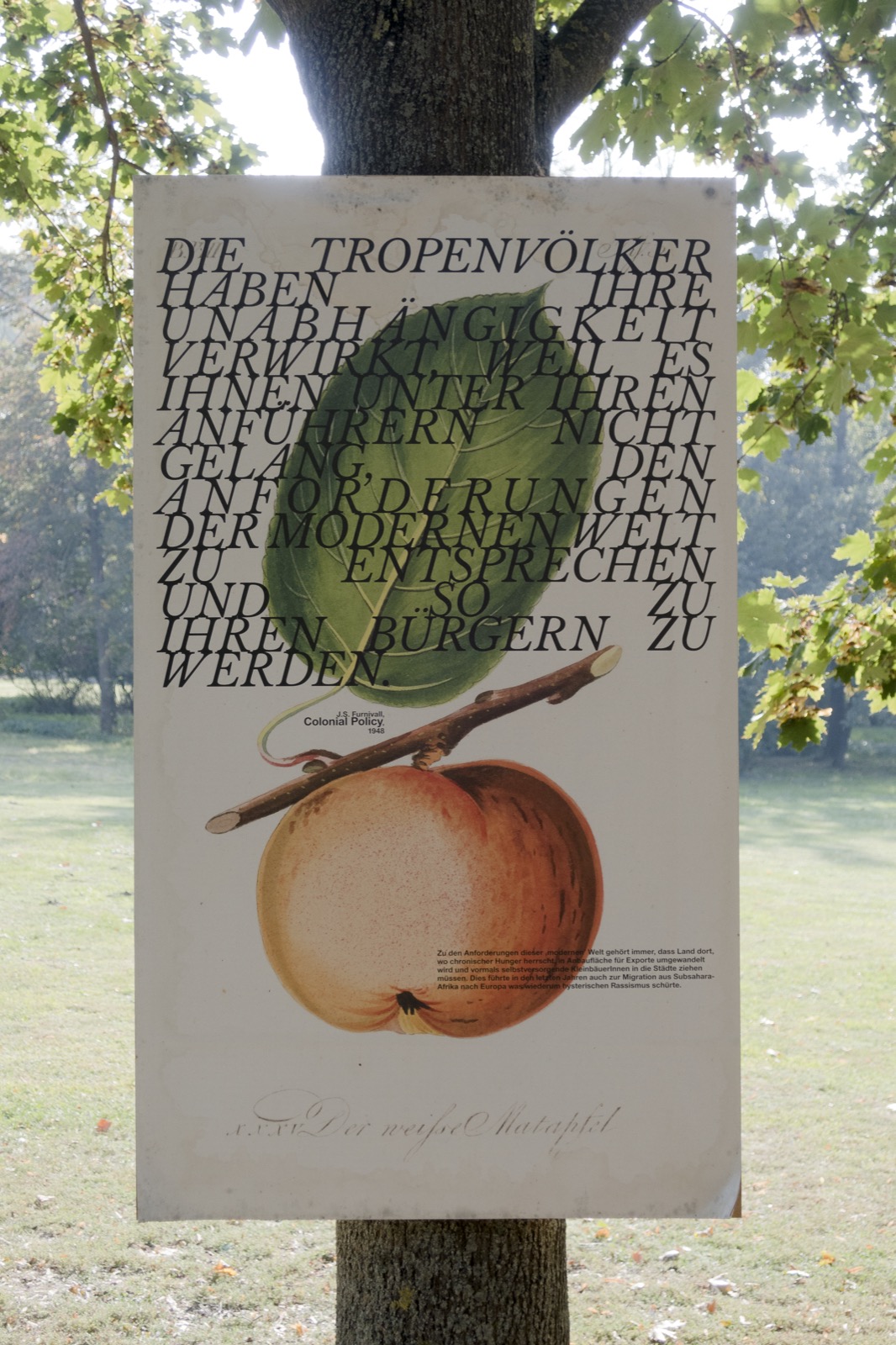

For ten years, from 2010-18, I was working on the artistic research into textiles from the Andean region called Loomshuttles, Warpaths. It was based on a collection of textiles and tools from the area that I had collected over travels spread over some 30 years. It aimed to weave together connections with wider global geographies, past and present, to reveal a world consisting of power, and exploitation, as well as by a multitude of resistances. This ‘eccentric’ archive wanted to challenge the ethnographic collections of the European museum, which continue to shape our perception of peoples and societies outside Europe. Consisting of 48 items, both ancient and modern, it is a travelling archive to make use in different places to develop alternatives to hegemonic knowledge production(s). The inventory of the collection takes the form of posters which are made up of visual interpretations of a specific item. Each is accompanied by four texts, two of which are designated on the posters; one sets up a timeline concerning worker struggles in the chains of textile and clothes production with specific dates; the others describe and reflect on specific textiles and colours as colonial subjects. The third set of texts are the visual and textual responses of artists, writers and practitioners to a particular textile in the collection, and the fourth are descriptions of these 48 items which are both aesthetic and contextual. All are made available in exhibition two books. A published book was also made. Currently, and over the last two years, Nathalie Boseul SHIN, the curator in chief of the Total Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul, South Korea, has, together with a group of students, been translating the large volume of texts into Korean and exhibiting the posters one by one. This is exciting for me since an initial work on textiles focused on fires in its factories had appeared at the 2012 Busan Biennale and which featured the self-immolation of Chun tae-il and heroic union organising in the textiles sector during the so-called Korean `economic miracle‘ under two dictatorships.which was based on the uber-exploitation of women in sweatshops which Chun was protesting in his action.

How is the curatorial embedded in your work? For example, do you see working with a curator in a museum as a collaboration?

I have seen myself very much as an exhibition artist and in both group and solo shows I have clear ideas of how I want the work to be presented and this involves dialogue and negotiation with the curator who is of course the one who has invited me. It is a process and involves the installation workers of the institution with whom there may also be negotiation as to how the work is to be realised. Recently for work presented at the Jakarta Biennale including 60 posters showing instances of ´land grab‘ over the last 500 years with basically the same rationalisations and ten t-shirts with designs celebrating international women land defenders, this dialogue – for budgetary and COVID reasons – had to be done by Zoom and with a lot of good-spirited to and-fro worked out well. I have also acted several times as a curator for a show called Utopian Pulse-Flares in the Darkroom which included 16 other invited artists groups. For this I created a SALON KLIMBIM kick-off in a huge circular tent in the Secession main hall, Vienna. It was a place for „Vegetarian tigers with no dress code of thought, no Frontex of contemporaneity and no utopia police, but party and performance, dance and madness, film and seduction, intervention and agitation, in short: negotiation and conversation“.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ComfyUI_temp_vplus_00001_.jpg

1066

1600

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2024-07-01 11:50:342024-07-01 13:52:18Vladimir Sorokin / The Future of Russian Dystopia

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ComfyUI_temp_vplus_00001_.jpg

1066

1600

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2024-07-01 11:50:342024-07-01 13:52:18Vladimir Sorokin / The Future of Russian Dystopia