Similarly, as Wagner theorised the Gesamtkunstwerk to support his artistic practice, Pyotr Pavlensky writes on ‘Subject-Object Art’, ‘events’, and ‘precedents’ in his essay ‘Terms and Notions’. The text is published in the catalogue of his first UK solo exhibition ‘Pornopolitics and Other Precedents’ on view at a/political’s new London space The Bacon Factory until 16 December. While many artists have bridged their way into art theory, only some have been successful in this endeavour. Beuys is one of the successful ones, or Malevich or Duchamp, with Andre Breton calling his ‘Green Box’, 1934, “a major intellectual event.” a/political similarly invited prominent writers such as Boris Groys, Sarah Wilson, et al. to contribute their thoughts to the exhibition catalogue and support the artist’s words. The question is, of course, is Pavlensky one of the obscure artists/theorists that did not survive their personal avant-gardes, or is he one of those who are to be canonised?

To pretend we can answer the above question, we need to pretend to understand its contexts and histories first. Pyotr Andreyevich Pavlensky (Leningrad, 1984) is a contemporary artist known for his controversial ‘events’. He studied at the St. Petersburg State Academy of Art and Design and has been called by some art historians a member of the third wave of Moscow actionists — after Kulik and Brenner in the first wave and Voina and Pussy Riot in the second. His works which he used to call ‘events of political art’, have previously included self-mutilation (‘Seam’, 2012, ‘Carcass’, 2013, ‘Fixation’, 2013, and ‘Segregation’, 2014), but have since mainly switched to acts of vandalism (‘Freedom’, 2013) or destruction of property (‘Threat’, 2015 and ‘Lightning’, 2017), until finally focusing on the purely online form in his latest still ongoing work ‘Pornopolitics’, 2020 –, and the new terminology ‘events of Subject-Object Art’. His work has not seen many exhibitions, with its artistic value being regularly disputed by the press and art theorists.

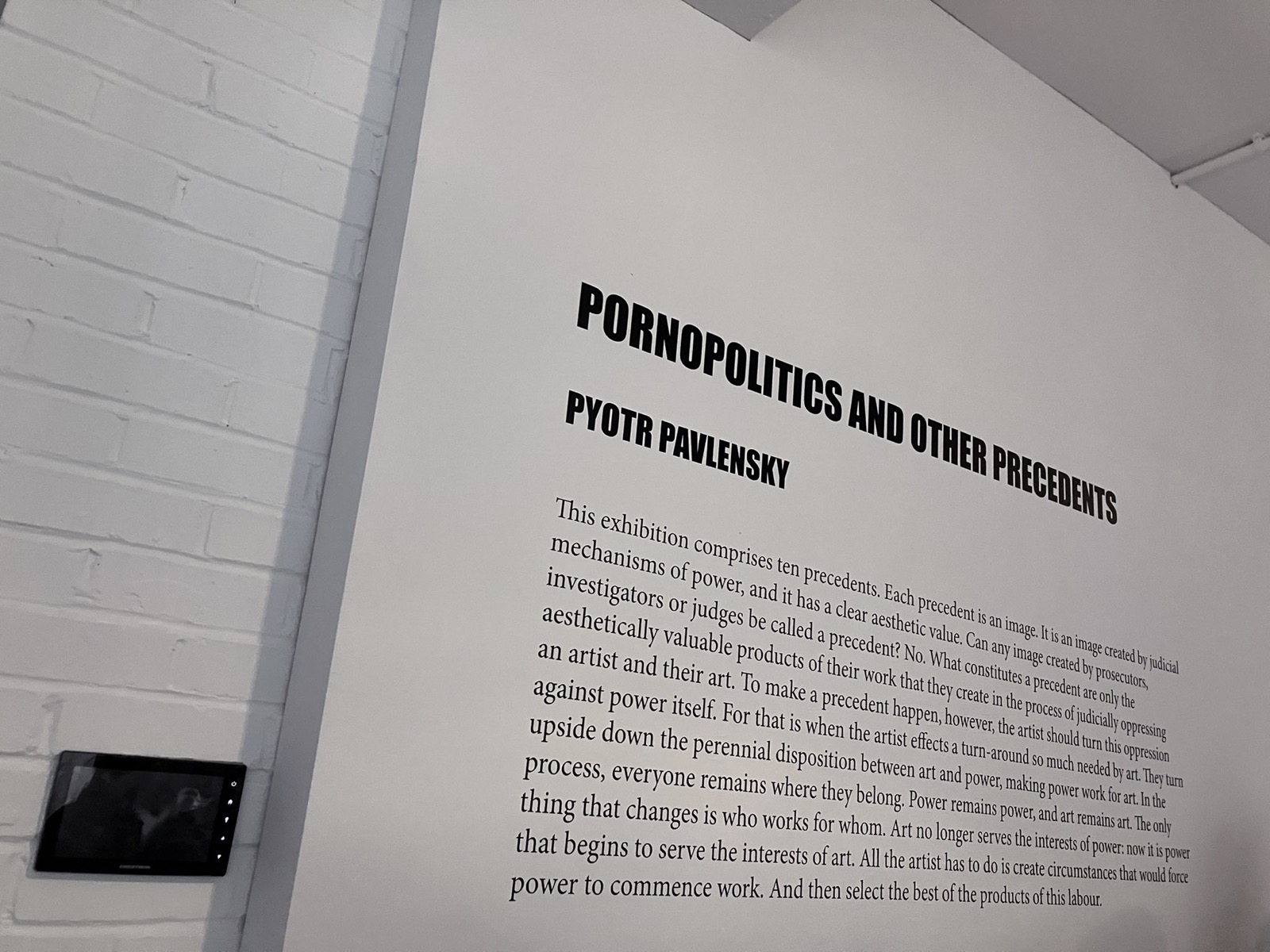

The exhibition ‘Pornopolitics and Other Precedents’ presents ten ‘precedents’, i.e. aesthetically valuable images that have been obtained by the artist from judicial mechanisms of power during criminal proceedings. The ten images are the outcome of Pavlensky’s latest three events of Subject-Object Art: ‘Threat’, ‘Lighting’, and ‘Pornopolitics’.

‘Threat’ was realised in Moscow on 9 October 2015 and consisted of burning the door of the famous FSB building on Lubyanskaya Square in protest of the illegal actions of the FSB against the Russian people. Almost exactly two years later, after being granted political asylum in France, ‘Lighting’ took place on 16 October 2017 and consisted of setting on fire the windows of the French National Bank building on Place de la Bastille. The building stands in the exact place where the Bastille stood before its destruction and now hosts the same bank that financed the 1871 Versailles troops’ recapture of Paris that ended in the loss of thirty thousand lives. The event, of course, was also almost a mirror image of the previous event in Moscow. Finally, the third event, ‘Pornopolitics’, was realized online on 12 February 2020 in the form of the world’s first porn website featuring politicians and government officials — more specifically, launching with the sex tape of Benjamin Griveaux, Macron’s candidate in the 2020 Parisian mayoral elections. The pornographic nature of the work even led to a partnership with Babestation, a UK adult television channel and website.

In his essay ‘Terms and Notions’ Pavlensky explains the terms ‘Subject-Object Art’, ‘event’ and ‘precedent’ in detail:

“Subject-Object Art is based on the existence of the phenomenon of power. /…/ two components are necessary for power to exist: those who govern and those who are governed. These two components are called the subject of power and the object of subordination. /…/ it is about arranging a certain combination of circumstances, thereby forcing officials to proceed to exercise their powers of authority and thus to realise the artist’s idea. /…/ Through that, a subject of power becomes an object of art, and what turns them into an object is their own power of authority.”

“Works of Subject-Object Art are called events and precedents.”

“There is quite a significant difference between an event, an action, and a performance. /…/ A performance is close to the theatre /…/ it means using a prepared room, having an invited audience. /…/ An action is no longer theatre /…/ It does not require invited spectators and, consequently, does not need to be announced. /…/ Yet the idea of an action lies in its simplicity /…/ An event differs from an action in scale. No artist can realise an event of Subject-Object Art every week because an event produces a crucially different social effect. /…/ the main difference between an event and other, outwardly similar art is manifested in their consequences and scale.”

“Neither events nor the photo and video records of events are precedents. The only things that can constitute precedents are images or texts produced by power mechanisms in the process of oppressing an artist and their art. The artist takes no part in the precedent-making process. /…/ the artist only has to do two things: first, create circumstances that will force subjects of power to commence exercising their powers of authority, and secondly, at the end of the production process, select the best of their output.”

He then continues to list his early works as examples, particularly romanticising the event ‘Fixation’ and following up with the details from ‘Freedom’. Interestingly, the court transcripts of the ‘Freedom’ trial have been published as ‘Dialogues on Art’ on a Russian media site and used as the script for three theatrical productions. Again, his diction is clear — all his events follow an obvious set of rules, and all happen in the same form in a similar period of around two years: event > arrest > detention > investigation > trial > (prison) > precedent.

What is interesting, though, is Pavlensky’s relationship to politics. He states that his work “is based on redefining the disposition of art in relation to power” while clearly stating that he is not interested and does not follow current political situations in the space where he works. Boris Groys sees political art as twofold: “(1) critique of the dominant political, economic, and art system, and (2) mobilisation of the audience toward changing this system through a Utopian promise.” Pavlensky, on the other hand, speaks about overcoming the direct political reactionist connection to his work and transcending his art to a level in line with the political. He does not want to mobilise or offer an alternative. He sees art as a direct kontrapunkt to politics in the position of an apparatus of power instead of having a reactionist role as political art mostly does through art history. Bana Bargu, a History of Consciousness professor at the University of California, puts it beautifully: “For /…/ Petr Pavlensky, art is not an aestheticized commentary on politics. It is, rather, the expression of the political in aesthetic form.”

Sarah Wilson calls Pavlensky’s ‘Terms and Notions’ a manifesto. (She also says Pavlensky is mansplaining, but let us leave that for another occasion.) I agree (with both of the above). Teresa L. Ebert of the State University of New York writes, “the manifesto is writing in struggle. It is writing on the edge where textuality is dragged into the streets and language is carried to the barricades.” Artists have written manifesti since Courbet, some being more emotional, abstract, or poetic and some being theoretic, even scientific. Pavlensky’s manifesto fits the latter. Still showing signs of struggle, with elements of self-praise and enhanced aestheticization, Pavlensky sets fresh grounds for a new movement and opens the door to extensive research of the topic, in at least some part to be continued by himself in his upcoming book.

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/bannerAustin_HELENE_06.jpg

1047

1534

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2018-04-29 13:41:072018-04-29 16:07:23Helene

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/bannerAustin_HELENE_06.jpg

1047

1534

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2018-04-29 13:41:072018-04-29 16:07:23Helene