There seems to be a distinct attraction in your work to situations that confront human beings with their limits. Is fear, or risk, a necessary condition of your inquiry, a form of fascination, or merely an inevitable side effect? Did this attitude already exist in your early works, such as The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories, or has it intensified with your larger projects?

Risk is never the goal, but it’s often the atmosphere in which the work can unfold. I’m drawn to situations where the environment resists control. Temperature, pressure, or volatility remind you of your own limits. That threshold heightens perception; it’s less about courting danger than about entering a state of attentiveness that only arises when you know the ground beneath you carries the potential of change. That sensibility was present from the beginning. The Blue Fossil Entropic Stories already involved confronting the fragility of ice and the instability of a landscape. At the time, I wasn’t thinking of it as “risk” so much as a need to experience the material directly, to understand it viscerally and not only intellectually. As the projects have grown, whether in deep-sea expeditions, active volcanoes, or radioactive zones, the settings have naturally amplified those conditions, but the underlying impulse hasn’t changed. Fear or risk is not a performance strategy; it’s an inevitable companion when you try to meet a place on its own terms. It sharpens the dialogue between body and environment and leaves a trace that becomes part of the work’s texture.

Which of your artistic experiences has truly brought you to the edge of collapse? At what moment did you come closest to that breaking point, when body and mind began to falter?

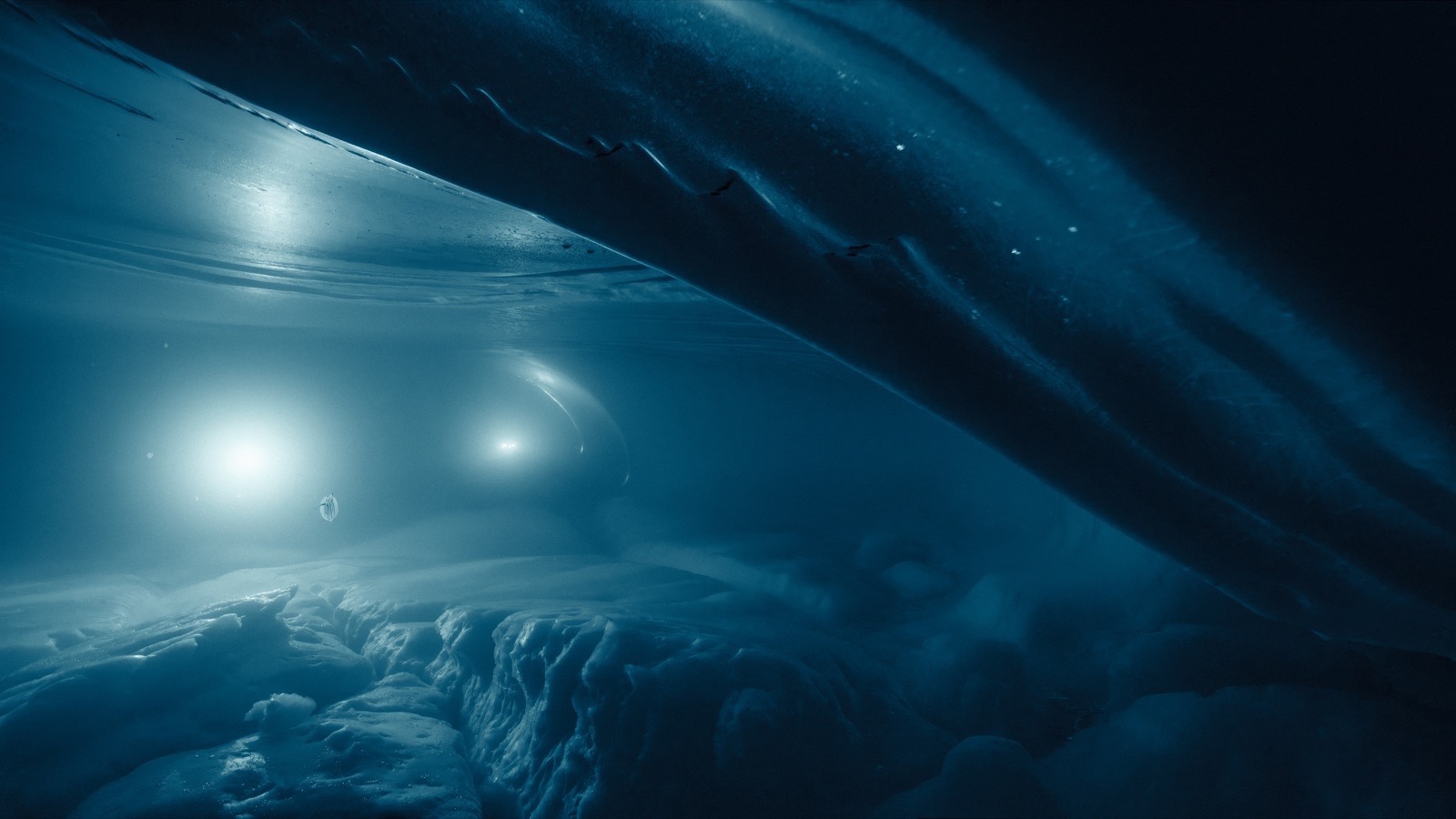

I wouldn’t say any of these projects pushed me to the edge of collapse, but there are moments when the environment simply overwhelms you, when you’re dwarfed by the landscape and forced to recalibrate. Sleeping in a tent on an ice cap at minus thirty degrees for a week, for instance, is less about heroism than about discovering how agile and adaptable the human body really is. Perhaps one of the most intense experiences came during the last shoot for my new film Midnight Zone. We were working eighteen-hour days and sometimes making three or four dives through the night, completely immersed in the ocean’s hypnotic darkness. The light from the fresnel lens held all my attention as some thirty silky and Galapagos sharks drifted around us. It was mesmerizing and dreamlike, but also charged with tension: wild animals, unpredictable currents, and absolute dependence and trust on the diver beside me. It’s in these moments, three hundred nautical miles from any landmass, when you know that a single current could carry you beyond return. It isn’t the subject of my work, exactly, but it is the kind of heightened, almost otherworldly intensity that sometimes arises as a side effect of the production.

Do you believe there is still a line between scientific inquiry and aesthetics, or is that division merely a false conviction, one that you have already dissolved in your practice?

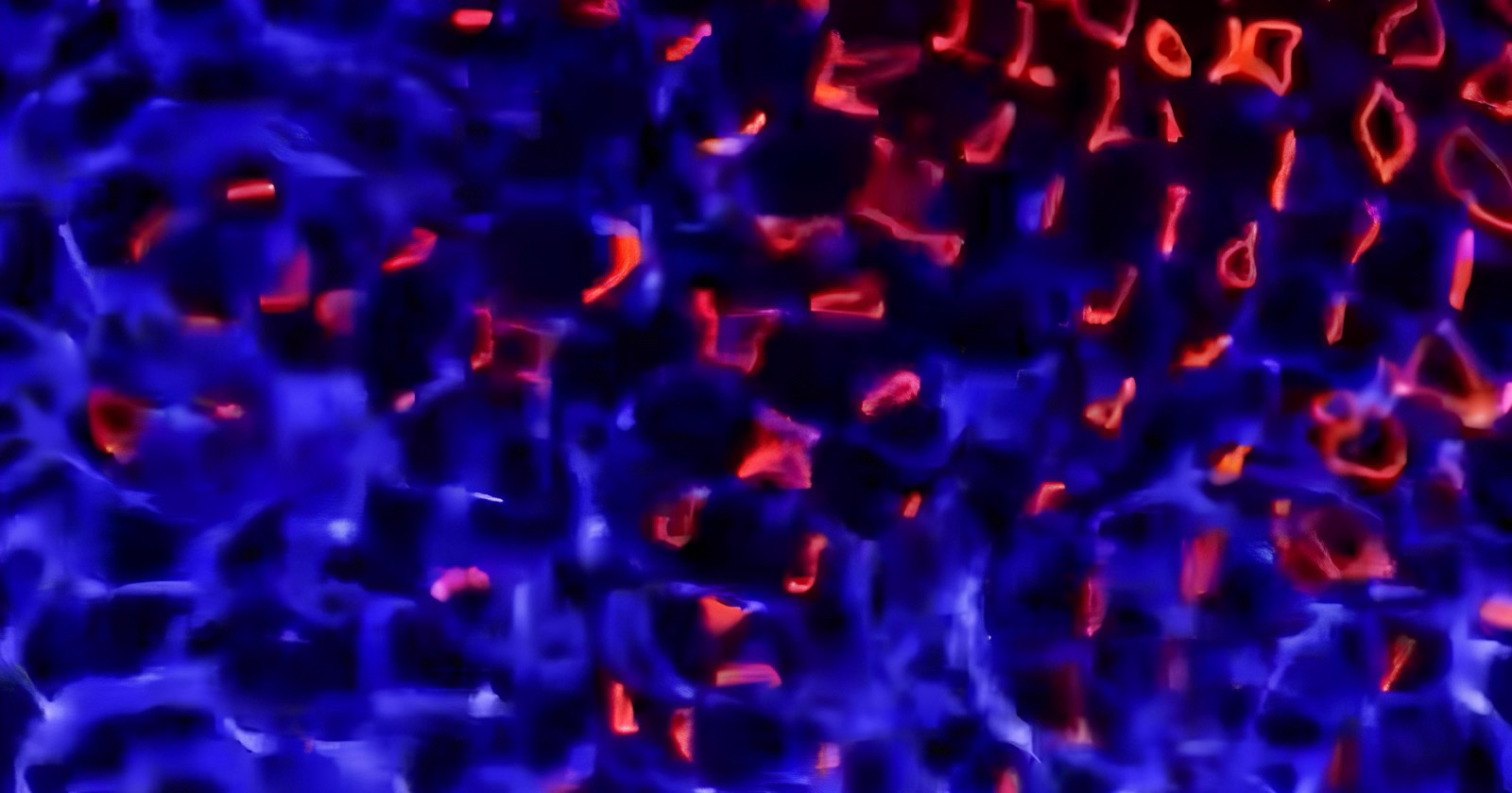

I don’t experience science and aesthetics as opposing realms. Science is often concerned with the how in terms of the mechanisms and processes of the world, while art is drawn to the why, exploring the poetic and existential questions those mechanisms provoke. Both are driven by curiosity and by doubt: in science, doubt is the engine of discovery; in art, it becomes a space for speculation and wonder. Science probes the world through measurement and experiment, while art translates those subjects into forms that can be felt and perceived through different modes—not only intellectually, but also sensorially and emotionally. The supposed line between them feels more like a convention than a reality. When the empirical and the poetic meet, something larger than either discipline emerges: a way of knowing that engages mind, body, and imagination at once.

Must art today employ trauma to break through indifference and redefine the relationship between humans and the world?

I don’t believe art must rely on trauma to reach people. Shock can be powerful, but it should not be the tool to expand our consciousness. What interests me is art’s ability to recalibrate how we experience the world: to slow us down, sharpen our senses, and offer keys to new understandings and ways of being. Rather than wounding the viewer, art can create moments of heightened attention and open space where subtle disquiet broadens our awareness. That shift in perception can be just as transformative as any confrontation with trauma, and perhaps more sustaining.

Many of your works seem to diminish humankind, stripping away its sense of omnipotence. Do you believe that the fracture of the ego is a necessary step in confronting the crises of our time?

I wouldn’t necessarily agree with the idea that I “diminish” humankind through my work. Humankind and its sphere of influence often remain central, yet its presence is felt mostly through traces, imprints, or after-images rather than direct figuration. What I try to question is the assumption of supremacy: by showing how our marks persist and entangle with other forces, I hope to open a space where we sense our embeddedness in planetary systems without needing to place ourselves at the center. As my work evolves, I’m more interested in repositioning our species within the larger web of life, turning away from the centralized gaze fixed upon us.

Do you ever fear that the aesthetic force of your works, burning ice, devouring flames, resonant deserts, might overshadow the scientific and conceptual dimensions that underpin them? Would you rather be recognised for the visual power of your images, or for the research that sustains them?

For me, the visual force is essential and will always be a portal through which people enter the work. I want the image to strike first, to create a moment of wonder or even disquiet that pulls the viewer in. But that initial impact is only the beginning. Beneath it lies the research: long conversations with scientists, field expeditions, and the slow accumulation of data, stories, and material that give the work its depth. I don’t see these layers as competing. The aesthetic intensity and the conceptual framework sustain each other. If the images didn’t resonate visually, the ideas might never reach an audience; if the research weren’t rigorous, the beauty would feel hollow. So I’d rather be recognized for both: creating experiences where visual power invites curiosity and the underlying inquiry rewards it.

In your practice, nature oscillates between power and threat, beauty and unease. How do you balance these polarities without succumbing either to pure spectacle or to simple admonition? And what is your view on acts of eco-activism that involve destroying works of art? Your pieces seem to suggest that it is possible to channel radical urgency without adding to the wreckage.

Nature is never just one thing; it oscillates constantly between awe and unease, resiliency and fragility. I try to hold those tensions rather than resolve them. If a work tips into pure spectacle, it becomes shallow; if it leans only toward admonition, it risks becoming didactic. My aim is to create spaces where beauty draws you in while carrying its own instability, so the viewer senses both attraction and vulnerability at once. As for eco-activism that targets artworks, I understand the urgency behind such gestures and believe they have their space and their reasons. But I’m against useless destruction. I’m more interested in transformation than in wreckage: in creating works that can hold radical urgency without adding to the debris. Ideally, the piece itself becomes an encounter, something that provokes reflection and dialogue, making the stakes of our ecological moment felt rather than simply shouted

Do you ever feel trapped by labels: “eco-artist,” “artist-scientist,” “visual activist”? Which definitions would you like to break free from because they obscure the essence of your practice?

Labels have never resonated with me; they risk oversimplifying. Terms like “eco-artist,” “artist-scientist,” or “explorer artist” can be convenient shorthand, but they flatten the complexity of the work and the relationships that shape it. My projects move across territories of geology, biology, history, and technology, and I’d rather they remain porous than be pinned to a single category. After all, the great strength of art is its viscosity. What interests me is the space where disciplines overlap, where doubt and curiosity guide the process more than a fixed identity. If a label is useful to someone encountering the work, that’s fine, but I don’t create with a definition in mind. I’d rather the practice stay open, able to shift and evolve.

Has your radical symbiosis with nature shaped you in your everyday life as well? What traces has it left on your body, your gestures, and your very way of being in the world?

I wouldn’t say that I live in a radical symbiosis with nature. If anything, like most of us, I inhabit a constant state of contradiction. Still, I have come to see that the supposed divide between “us” and “nature” is an illusion we’ve maintained for millennia. There is no great “outside.” We are nature as much as nature is us. Recognizing this doesn’t turn me into some perfectly harmonious being; it simply deepens my awareness of interdependence. To understand this is, in a way, to understand who we are and to keep choosing life.

What limit still remains to be crossed? Which frontier would you most like to explore next, in a personal work, or through an ideal collaboration?

Since Midnight Zone and many of my recent projects, I’ve felt an enduring pull toward the deep sea, that lightless realm where life follows logics we can barely imagine. I want to keep pushing that research forward, perhaps even return in a submersible. The last time I descended underwater in such a craft, I was a child on Lake Geneva; revisiting that experience now would feel like crossing a true frontier. What fascinates me is how the deep ocean resists our usual ways of knowing. Its darkness is physical but also cultural: a space we can’t easily tether to familiar narratives or even measure in human terms. Entering such a world forces a different kind of attention. One where the senses are strained and time itself feels elastic. For me, that’s the next threshold: to keep working in direct contact with a place that remains largely beyond reach, and to find artistic forms that convey its mystery without domesticating it.