I had the pleasure of working with you a few times so far. How would you describe your multidisciplinary practice?

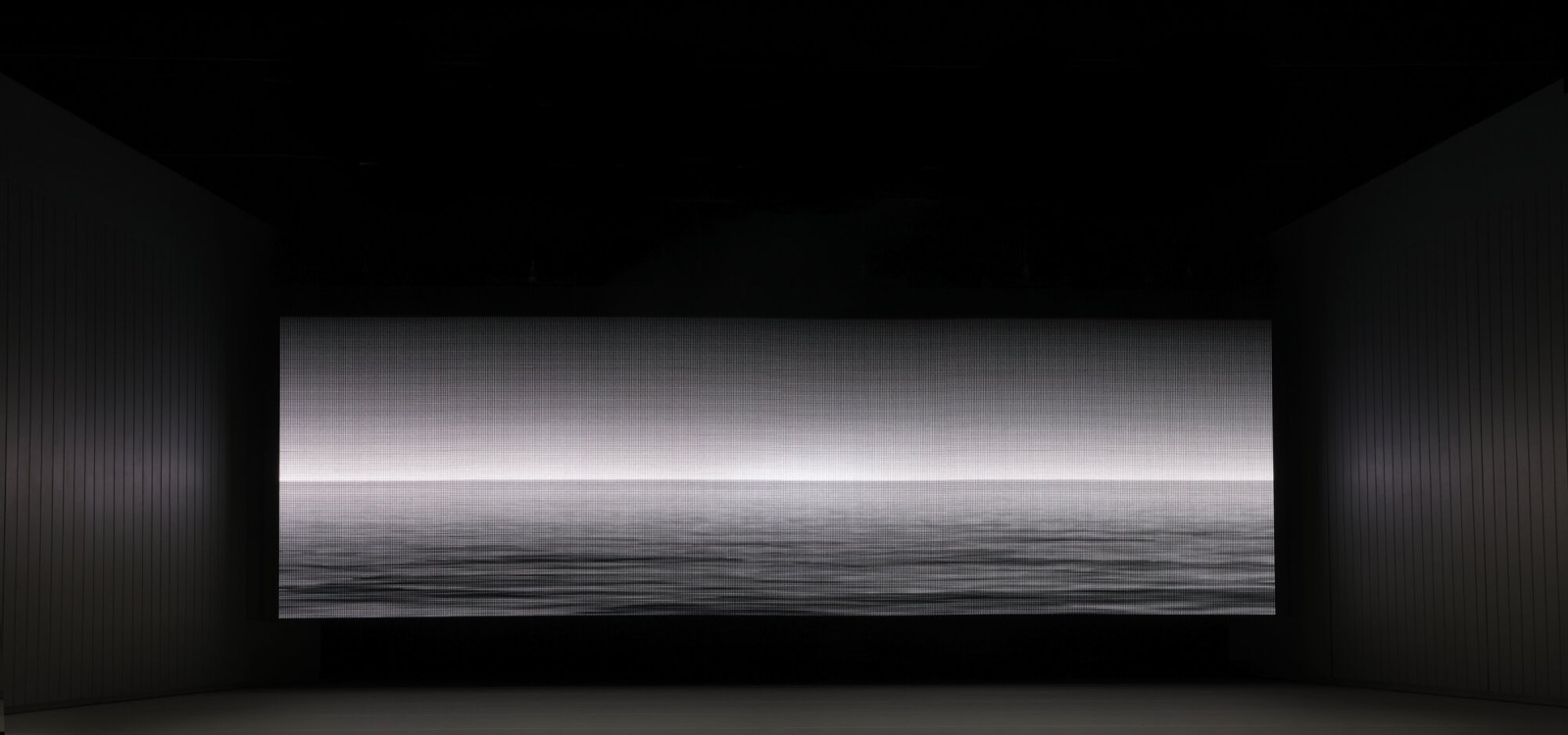

I have a noisy brain, my work is often driven by a need to find silence from continual questions. I am fascinated by the physical presence of the world: cities, landscapes, architecture, technological objects. I would probably say I am more interested in the spaces that people create rather than people themselves. In a sense, physical manifestations of a collective brain rather than the individual. With this in mind, the landscapes where the absence of human activity is apparent are equally striking. I see these spatial typologies as a manifestation of our own human condition: in a similar way to the phrase ‘God created the world in his own image’, we as humans created the world in our own image, so the world we inhabit is a reflection of ourselves. The built and non-built. There is a wonderful intersection between space, technology and landscape that I have been probing recently. I am interested in documenting, observing and recording, which result in a range of different mediums, from installations, sculptures, photography and film in the form of fragments from these shattered landscapes. Photography is the engine of my work, a documenting and reordering of the world to bring new connections and meanings to me to form works in other mediums. Everything to me exists in life within a state of transition and uncertainty, existing in the in-between, on a constant threshold, so I try to reflect that in the way I make work as well, moving from one medium, one mode of display to the next. I love the idea of having work shown in a gallery then in a theatre, then perhaps online, loosening conventional labels and structures.

Your work is connected to climate problems, how do you think art can influence people’s mind on this topic?

As much of my work has a preoccupation with landscape, climate has a critical role in the formation of that, in the same way that I see cities as a human creation, these effects on landscape are also a human creation. So these changes are a symptom of our own human actions and in some regards our obsession with technology and the advancement of humankind through technology. This big shift in our world, due to the changing , to me is part of a wider conversation that stems from a care of the self. We tend to see the world as other to ourselves, but we are inseparable, the self-destructive nature and disregard for human life that manifests through poverty, war and inequality also then seeps into the world we inhabit. We live in the short term and many of our lived spaces reflect that; beaches curated around hedonistic desires, basking in the sun, while the world heats up and the water levels rise. However, that being said, personally, I don’t really think it’s an artist’s place to influence, rather raise issues to enable debate, discussion and amplify. The end result will be what it will be. If we collectively decide to act then we do, if we don’t we don’t and so be it. The world will be fine, it’s humans that won’t be. I’m slightly nihilistic in that sense. Often there are personal concerns I have about the world that naturally manifest within my work, I just hope someone will discuss them with me. It’s often the curator’s job to bring issues to the surface, to create shows and commission work that is relevant, and as a result create platforms for discussion. It’s interesting at the moment how few shows discuss the environment, despite it being one of the biggest threats to humankind that has existed.

You were and are involved in many public art projects, what are the difficulties of public art from an artist’s point of view? Could you talk about projects you did?

In my opinion, the main difficulty with public art is context; the context can shift drastically depending on the time of day, season, use of that space, so that work has to withstand the lack of control you might have within a gallery, for instance. It’s so unpredictable. Alongside this, the people viewing your work might not have any knowledge or interest in contemporary art, so it has to connect to them in some way. I was looking at a well known statue recently when a man walked up to it, put his sunglasses on the statue and took a selfie, is that 21st century connection?

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/L.E.V.hyperdigitalexperience-008.jpg

1600

1600

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2023-11-15 12:33:072023-11-15 12:38:06L.E.V. / Hyper-Digital Festival

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/L.E.V.hyperdigitalexperience-008.jpg

1600

1600

Editor Nasty

https://www.nastymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/new-logo-basker-WHITE4.png

Editor Nasty2023-11-15 12:33:072023-11-15 12:38:06L.E.V. / Hyper-Digital Festival